Last year, on our way back from Himachal Pradesh, we had stopped briefly at Ibrahim Lodhi’s tomb in Panipat, and, even more briefly, at a kos minar near Karnal. While it had not been especially impressive, it had, inspired me to see more of Haryana. After all, I’ve lived in Delhi and around for nearly forty years now: it’s unpardonable to have seen so little of one of our neighbouring states.

This year, we’ve realized it may not be possible—given various exigencies—to go for a week-long summer vacation. A brief road trip is all we might be able to manage. It seemed a good time to try exploring Haryana. Hisar, we decided, with a stop en route at Rakhigarhi.

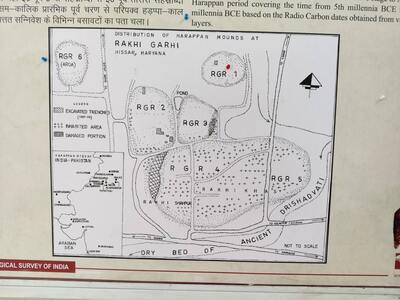

Rakhigarhi is not just one of Haryana’s, but of the Indian subcontinent’s, most exciting historical sites: the home of what is now believed to be the largest Indus Valley Civilization settlement. Larger even than Mohenjodaro, Rakhigarhi stretches across two modern villages, Rakhi Khas and Rakhi Shahpur. Villagers here still find ancient pottery shards, beads, calcified bone and more in their fields, but the actual work of the ASI began in the 1960s, with excavation that goes on to this day. Eleven mounds stretch across the Rakhigarhi area, of which we visited three.

Getting to Rakhigarhi’s mounds proved difficult in a car: Google Maps isn’t very good at showing motorable roads, and was intent on leading us into narrow two-buffalo lanes. Finally, after much asking about and a bit of a wild goose chase, we landed up at Mounds 2 and 3, which are next to each other.

We entered Mound 2 first, and though we walked about for a while, there was nothing to be seen here except “pigs, dogs, and mounds of cow dung,” as our ten-year-old daughter, the LO (‘Little One’) described it. She wondered if the mounds of uplas (dried cow dung cakes, used for fuel) was what the ASI meant when it mentioned ‘mounds’.

Mound 3, just across the lane from Mound 2, was an improvement: it had a large section covered with plastic roofing, which was for us a treasure trove: this was an excavation, and we saw not just sunken walls and a well (a very narrow-mouthed well, so narrow that the LO was sceptical about it being a well at all).

Even more thrilling: there was a skeleton here, nearly—or as far as we could see—complete. A little closer peering, and we noticed even more bits of stray bones in nearby walls. Mound 3, we read in the plaque at the gate, had partly been a burial ground.

This, however, paled into relative insignificance in comparison to Mound 1. Mound 1 is very large, and work is ongoing here: one side of the area, at the foot of the mound, is taken up by the tents in which the archaeologists live (and presumably have their offices). There’s a small and rather basic Exhibition Hall at the entrance which shows a map of the excavations at Rakhigarhi, the locations of the mounds and so on:

… and the mound itself has excavations all across the top. These were covered with tarpaulins and the guard at the gate told us that photographs weren’t allowed in that area, but we got a peek, at least, and saw rooms, walls of brick, and so on, all excavated. At the base of the mound, a group of local workers (all villagers) were on their haunches, carefully brushing away at the grassy ground. All around them, carefully placed on a well-marked grid, were neat heaps of artefacts: pottery shards, mostly. The LO was quite impressed; the patience required to do work like this was new to her.

Before we moved on from Rakhigarhi, we also made a brief detour into the village (this was unplanned; we got lost) and chanced upon a slice of history: a ‘wall’ like a cliff face, pockmarked with holes in which pigeons and parakeets nest—and with bits of old pottery clearly visible here and there. The contrast with modern Rakhigarhi, just a few feet away, was quite stark.

Rakhigarhi was an amazing experience. We didn’t get to see a whole lot of stuff, but what we saw (and what we imagined) was quite extraordinary.

That night, we stayed at the Lemon Tree Hotel at Hisar, and next morning, set off to do some sightseeing around the city before heading home.

Hisar has been around for a long time, the principality it once formed being a part of the realms of rulers such as the Tomars and Prithviraj Chauhan. It wasn’t until 1354 CE, however, that this city was given its present name: Firoz Shah Tughlaq built a walled fortress here, which he named Hisar-e-Firoza (‘Fort of Firoz’). The fort was extensive, with four major gates and palaces, granaries, stables, a mosque, and more. Hisar was to go on to greater glory in Mughal times, becoming an important strategic centre. In the late 18th century, the town became part of the jagir of an interesting character, an Irish adventurer named George Thomas ‘The Raja from Tipperary’. Thomas, whose name got locally distorted to ‘Jahaz’, held sway in Hisar and nearby Hansi for three years, from 1798 to 1801.

That, then, was the area and the times we were setting off to explore.

Fortunately for us, pretty much everything we wanted to see was within a small area, centred round Firoz Shah’s Palace. This is part of what had once been the citadel and of which only very little remains. Google Maps threw us a googly here, sending us down a series of narrow lanes that skirted round the outside of the fort, but didn’t actually go in. After about 15 minutes of fruitless wandering, we finally met someone who knew the exact way to get to the fort: on the main road near the bus stand.

There’s no entry fee for the fort (or for any of the other monuments we visited in Haryana, for that matter). There is, sadly, also not very much information barring a stone plaque at the entrance. This mentions the granaries, the underground chambers, stables, and palaces that were once part of this complex, but when you actually wander around, you don’t see exactly what was what, because nothing is labelled. We could only surmise.

The one structure that is labelled, however, is the picturesque Lat ki Masjid. The ‘lat’ (‘lathi’, or long stick) being referred to is an Ashokan pillar edict that had been originally erected in Meerut during the 3rd century BCE by Ashoka the Great. Firoz Shah Tughlaq was fascinated by this pillar (as he was by another Ashokan pillar, found at Khizrabad and subsequently transported at Tughlaq’s orders to his Delhi citadel of Firoz Shah Kotla). The Meerut pillar was brought here to Hisar, and though the bottom part of it (now highly eroded) still retains part of the original inscription, the upper portion is of carved red sandstone that Firoz Shah added on.

Beside the pillar is a small domed building, and on the other side, an unusual L-shaped mosque. The mosque’s carved stone columns may have been reused from old Hindu or Jain temples.

The other important building that would have been part of Firoz Shah’s palace complex is the Gujari Mahal. Because the palace complex is anyway half-ruined and modern roads and buildings have appeared in the spaces that might once have been occupied by palace buildings, the Gujari Mahal is now approached through a separate gate of its own, a little down the road and along a perpendicular lane.

Gujari Mahal is supposed to have been built by Firoz Shah for a gujar (nomadic) woman from Hisar whom he fell in love with. Firoz Shah, it is said, proposed to her and wanted her to accompany him back to Delhi; but the woman, too fond of her home town to leave, refused—so Firoz Shah Tughlaq built the Gujari Mahal here for her. It’s a rather spartan but elegant arched pavilion, its battered walls and sparse decoration very typical of Tughlaq architecture. Just behind the pavilion is a smaller brick chamber, obviously of much later provenance, which has a few cenotaphs in it. Whose these are is unknown.

There was one last place we wanted to see in Hisar: Jahaz Kothi, once the home of George Thomas (‘Jahaz Sahib’, see above). Google Maps, however, sent us all over the place again, and finally (it was nearly noon, and we had at least four hours of travel to get home, besides another sight) … we decided to give up trying. Maybe someday, en route to some other place, we’ll stop by in Hisar long enough to see Jahaz Kothi.

The last sight on this trip was at the town of Hansi, 31 km from Hisar. This is home to Hansi Fort, also known as Asigarh; more popularly, it’s called Prithviraj Chauhan’s Fort—a little inaccurately, given that he was not the one who originally built it, and was not even its only lord and master. The fort has a long and interesting history, having been held at various points of time by (other than Prithviraj Chauhan) the Marathas, George Thomas, and even the famous Colonel James Skinner. Skinner, in fact, raised his regiment, Skinner’s Horse, at Hansi.

Like everywhere else on this trip, here too there was nothing to explain what was what. In fact, in comparison to places like Firoz Shah’s palace complex and Gujari Mahal (which at least had a plaque that gave you some idea of what the place was about), here there was not even that. It took a good bit of post-trip researching for me to find out something about Asigarh, primarily from this blog post, which appears to be fairly well-researched.

The gateway of the fort is a very striking one, more so because of how unusual it is. This one, all towering brick, was built by George Thomas when he controlled Hansi.

Beyond the gate, a paved path ascends to a sort of plateau which is dotted with thorny trees, shrubs, and a few buildings. There were bee-eaters and silverbills, lapwings and wagtails here, and the LO (who, like me, is a keen birdwatcher) was in seventh heaven.

The first building here was a half-underground one, rather gloomy, with rows of pillars inside. This is locally known as the ‘baradari’ (‘twelve doors’, a word used to describe pillared pavilions, though this one would have many more doorways than just twelve). It’s believed that this baradari was once used to store ammunition.

Further on from the baradari, we passed a platform with a few cenotaphs atop it, and then, off to the left, a large flat-topped building that we guessed might have been a well (or a baoli, a stepwell) since it had a typical sloping wellhead, designed to take a bar on which a rope could be slung to work as a pulley. The LO went to examine this with her father, but the place was closed on top.

Last of all the structures we could visit in the fort was an enclosed (now only partly enclosed; the wall has mostly crumbled) area that contained a couple of domed buildings, a newly painted tomb, and a small herd of goats. The two domed buildings seem to be popularly referred to as ‘Mama-Bhanja ka Gumbad’, an allusion to the relative sizes of these: the ‘Mama’ (uncle) being the larger-domed, the ‘Bhanja’ (nephew) the smaller.

In reality, these are two mosques, both dating from at least the 17th century. The Jama Masjid is the larger mosque, the Moti Masjid is the smaller. Beside the Moti Masjid, the gaudily painted tomb is that of a local peer or holy man named Miran Sahib.

Between Jama Masjid and Moti Masjid, a stretch of wall still remains of what would once have been the peripheral wall of a sarai, a travellers’ inn. Very little of this exists, barring a couple of rather beautifully carved pillars which, I’m guessing, were reused here.

From this sarai, at the far end of the fort, we made our way back out to the main gateway and from there, into our car to head back home.

It was a wonderful trip: short and sweet, a good break from the humdrum of daily life. I’m determined, now, to explore more of Haryana.

Having read Col James Skinner’s book and about Skinner’s Horse, the moment I first read the name Hansi here, I said that’s Skinner’s place! Sad to know that Google doesn’t guide or lead one to the places accurately but then that’s part of the adventure as well! The ASI needs to do something about it as well to make it interesting for people to come visit such places. Only then will we learn more about our past and vast history and culture.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really think Haryana Tourism (along with the ASI) needs to shift its focus from letting Haryana be just a state you travel through on your way to more interesting places. There’s a lot of history here, and if they’d just improve the tourist infrastructure (plus, of course, provide a good deal more information!) it might change things a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is so interesting. Didn’t know Hisar had such fascinating monuments. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! Thank you for reading. :-)

LikeLike

Looks like an interesting place to visit. Will try to visit it sometime in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do visit. I enjoyed this a lot.

LikeLike

I am with the commentator above. Had no idea that Hissar had such an interesting history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haryana, as a whole, has been a fairly active place as far as history goes – several important battlefields are here, for instance. It’s a shame that the state does so little to promote itself or its many historical monuments (perhaps they don’t even realize what a treasure trove they’re sitting on).

LikeLike

What an interesting journey that was, Madhu, to read your account of this short trip – I felt like I’d travelled with you and ‘seen’ these places for myself. Lovely!

I haven’t seen much of the North at all – well, to be frank, not much of anywhere at all. We finally began travelling last year, hope to continue doing so while we are still able to. Bookmarking your travelogues for future reference. In the meantime, I’ll continue to ‘sightsee’ with your posts. :)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed this, Anu!

And re: your sightseeing in the North, I suppose that’s fairly true of anybody who’s spent most of their time living in one part of the country (or, of course, in your case abroad). I have seen far, far less of the Deccan Peninsula, Bengal and the North-East than I wish I could have, and I’ve actually never been to Odisha or Bihar. :-( So much to see, so little time.

LikeLike

The older I get the less inclined I am to travel, but I like “going along” with you and your family through your writing. Continues my education too. I now know who George Thomas was, and what a cenotaph is!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed this.

I had heard about ‘The Raja of Tipperary’ before but had forgotten all about him by the time we planned this trip. All of it was brought back to me when I did the research for it. I do wish we’d been able to see Jahaz Kothi, though.

LikeLike

congrats for the unholy drought

I read about it on scroll today, and the premise looks interesting

also no blog today?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I was very busy yesterday, so didn’t publish a new blog post. But will do that later today.

LikeLike