When I first began searching the Net to find landmark regional films to review for this special ‘100 years of Indian cinema’ celebration, Chemmeen was one name that cropped up again and again. It sounded impressive. This was one of the first Malayalam films to be made in colour; more importantly, in won the President’s Gold Medal for Best Feature Film at the National Film Awards in 1965. It was screened at both the Cannes and the Chicago Film Festivals, and was greeted with much critical acclaim (not to mention commercial success)—it was even released, dubbed, in Hindi as Chemmeen Lehren, and in English as The Anger of the Sea.

All it needed was for me to discover that the music director of this film was an old favourite (Salil Choudhary) and that Manna Dey sang in it, and my mind was made up: I had to watch Chemmeen.

Based on a very famous novel (written in an astounding three weeks!) by Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai, Chemmeen (‘Prawns’) is set along the Kerala coastline, in a community of fisherfolk. The film opens on the seashore, as the fishermen get their boats out to sea, rowing, swinging their nets out, hauling in the catch, bringing it ashore, and sorting it.

Among these is the middle-aged Chembankunju (Kottarakarra Sreedharan Nair) and his friend and neighbour Achankunju (SV Pillai). Achankunju is a happy-go-lucky man who spends most of what he earns on drink, which leaves his wife Nallapennu (Adoor Pankajam) thoroughly irritated. They have no children, which means Nallapennu has plenty of time to nag her husband and try and get him to mend his ways.

Chembankunju’s household consists of his wife Chacki (Adoor Bhavani), and his two daughters, the beautiful Karuthamma (Sheela) and the teenaged Panchami (Lata).

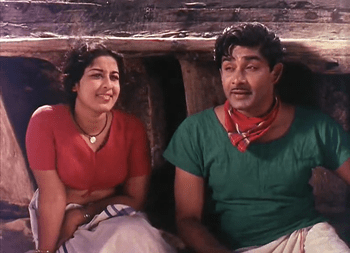

In the scene where we are first introduced to Karuthamma, she is sitting beside an upturned boat on a secluded part of the shore, chatting with Pareekutty (Madhu). Even though their conversation is innocuous enough—she tells him that her father wants to buy a boat and a net, and will Pareekutty please lend him the money—it’s obvious that these two are in love. Their eyes say it, even if they do not put it into words.

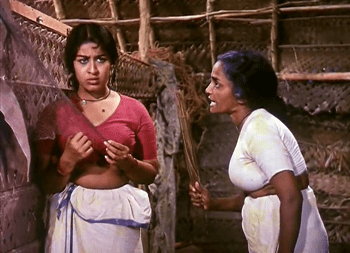

Panchami, sent by her mother to fetch Karuthamma home, returns without her sister. It’s only when Chacki emerges from their hut and starts yelling for Karuthamma that Karuthamma scrambles up and rushes back home—where Panchami tells Chacki that Karuthamma has been with Pareekutty. Pareekutty is Muslim, and therefore, not a man Karuthamma should be meeting, since nothing can ever come of it.

In a diatribe which forms the crux of the film, Chacki yells at Karuthamma: for them, the fisherfolk, the ‘Sea Mother’ provides all they need—as long as they, the women of the community, keep a hold on their morals. If a woman slips and yields to an illicit passion, the Sea Mother will inflict a terrible punishment: death. Any fisherman whose wife is unfaithful will fall prey to the sea.

Shortly after, Chembankunju—who had been planning to ask Pareekutty for a loan—goes to meet the young man. Pareekutty is a trader (from what I can see, he owns a small outfit that dries and sells fish and prawns) and is wealthier than Chembankunju.

Chembankunju needs Rs 450 for the boat and net (he knows of someone who wants to sell the boat, and that is about how much Chembankunju is willing to pay).

Pareekutty, because of his love for Karuthamma, agrees. Chembankunju and he discuss the deal through: how will Chembankunju repay the loan? They finally agree that all the catch that Chembankunju brings in in his new boat will be Pareekutty’s until the value of the loan has been repaid.

Only, Pareekutty has no money to lend Chembankunju; will dried fish do instead? He can deliver basketloads to Chembankunju’s home that evening, and Chembankunju can sell it and use the money. Chembankunju is more than happy. That evening, Pareekutty delivers the baskets.

The next day, Chembankunju hurries off to the house of the man whose boat is on sale. He is given a warm welcome, buttermilk to drink, a stool to sit on, and a taste of just what it might be to be wealthy. The man’s wife—perhaps just a few years younger than Chacki, probably, since her son is a teenager—is elegant and well-dressed, too, and Chembankunju is impressed.

This is how he wants them to live, he tells Chacki when he gets back home with the new boat. They should be living in style.

The next morning, Chembankunju begins to show his true colours. His dear friend Achankunju, who had been certain that he would be among the first to be welcomed onto the new boat, finds himself left behind…

…and when the boat comes, full to the brim with the catch, everybody comes crowding around. A bubbly Panchami reaches for the fish, asking her father if she can fill up her basket—only to have him beat her and tell her to get lost, this fish isn’t for her. Panchami bursts into tears, and Chacki and Karuthamma try to console her.

Onto the scene comes Pareekutty, who, by rights, is the owner of all the fish that Chembankunju has brought in. But when he asks if he can take the fish, Chembankunju pretends complete ignorance of that verbal agreement. “Do you have the money for the fish? I want ready cash for it,” he tells the young man, as if Pareekutty wants to buy the fish, not claim what is really his.

Pareekutty does not have any money, and Chembankunju shoos him away. And Pareekutty, too polite (and too much in love with Karuthamma to accuse her father of reneging) goes away.

The days pass. Chacki pleads with her husband to return Pareekutty’s money. After all, the boat and the net are bringing in lots of fish, which translates into increasing prosperity for the family. They’ve managed to buy new furniture, and when the monsoon stalls work for the rest of the fisherfolk, Chacki even has enough money to loan to her neighbours (against surety—a brass lamp here, a small metal pitcher there).

Karuthamma doesn’t like this idea of accepting surety, at least not from dear friends like Nallapennu. Chembankunju didn’t give any surety when he borrowed from Pareekutty, she points out bitterly to her mother, but Chacki—her head also somewhat turned by all this wealth—isn’t listening. Even though she too agrees that the loan should be returned to Pareekutty.

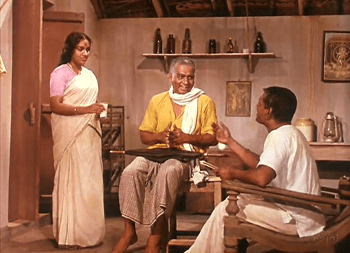

Meanwhile, Chembankunju has made the acquaintance of Palani (Sathyan), a fisherman who works on Chembankunju’s boat. Palani is no great catch: he’s very poor, he has no family or friends to speak of; he even admits—and with no compunctions—that he sleeps on the beach and spends whatever he earns on food.

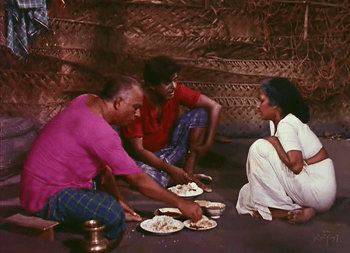

Chembankunju decides that Palani would make a good match for Karuthamma (he seems to hope that Palani will agree to live with them, which will let Chembankunju retire). He invites Palani home for a meal, and he, along with Chacki, proposes the match to Palani.

Palani agrees, and Karuthamma, though she is distressed, really has no choice. Pareekutty, being a Muslim, can never be hers. And she has to be a good daughter; she cannot defy her father.

She does, however, put her foot down on one matter. She will not, come what may, stay on in this village. Palani belongs to a village some distance off; she will go there with him. (Karuthamma realises that living in the same village with Pareekutty will be painful for both of them).

So Karuthamma and Palani are married. Just as the wedding ceremony is completed, Chacki suffers what seems to be a stroke. Karuthamma decides to stay back, but Chacki—who knows how much anguish that will cause her daughter—begs Karuthamma to go. Snowed under by this emotional blackmail, Karuthamma finally agrees to go—only, this time, Chembankunju (who is oblivious of Karuthamma’s feelings for Pareekutty and has no idea why she wants to leave the village) pleads with her to stay for her mother’s sake.

Karuthamma does depart, in tears, but leaving behind a father who’s so irate, he refuses to have anything further to do with his newlywed daughter.

And Karuthamma also leaves behind, grieving for her, a ruined Pareekutty. His business has fallen apart, and despite many pleas from his father (who comes visiting now and then), Pareekutty refuses to leave the place and go back to a more comfortable life.

In Palani’s village, Karuthamma settles into married life. Palani may not be a fine husband; he may not be the man she wanted to marry—but she is a dutiful (even affectionate) wife. The only thorn in their flesh is the fact that the other villagers are suspicious of Karuthamma. Why did a woman so beautiful marry a worthless no-good like Palani? She must be characterless, say the women; and soon, rumours spread linking Karuthamma with Pareekutty. Karuthamma and Palani find themselves being ostracised…

…while, back in Karuthamma’s own village, things are swiftly beginning to deteriorate, both for Karuthamma’s family and for the inconsolable Pareekutty.

What I liked about this film:

Everything, actually. The story is simple and sensitive, and presents a common trope—that of a forbidden love—in a way that is touching yet not over the top melodramatic. The film is beautifully scripted (TS Pillai was involved in writing the screenplay), very well-acted, and well-directed (by Ramu Kariat). Incidentally, one of the editors of the film was another familiar name: Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

One thing that I liked in particular was the way the characters were drawn: in shades of grey rather than black and white. Chembankunju, for example: while his greed and ambition do get the better of him for a while, he is fond of Chacki. And while he may not be the best of fathers, he’s not completely neglectful, either.

Also, I like the way in which Palani and Karuthamma’s marriage is handled: unlike the more typical Hindi film way in which such unwanted marriages tended to be shown, Karuthamma neither:

(a) refuses to have anything to do with her husband; nor

(b) completely forgets Pareekutty

Instead, in a very human, very realistic way, she reconciles herself to being as happy as she possibly can as Palani’s wife—but it doesn’t mean that she has forgotten Pareekutty, or even her love for him.

Also noteworthy is the subtle way in which emotion is shown. For example, there’s a scene where a still-unmarried Karuthamma goes to a deserted pond with two earthen pitchers to fill water. Pareekutty arrives, and confronts her, asking her if she loves him. She admits it, but somewhere there lurks the fear of the Sea Mother’s wrath, and Karuthamma retreats. She does not say much, but in the way she moves—hesitating, moving away, stopping—you can literally see the conflict within her. And Pareekutty loves her too much to force her, so he struggles with himself too.

And the music, by Salil Choudhary (Chemmeen was his debut Malayalam film). Among my favourites are the haunting, oft-repeated Manasa maina varo (sung by Manna Dey) and Puthan valakkare (in which people familiar with Hindi cinema music are likely to find more than a passing resemblance to Baagh mein kali khili, from Chand aur Suraj, also composed the same year by Salilda).

Finally, the stunning cinematography by Marcus Bartley. The entire feel of the film is very evocative of a real fishing village, not a constructed set; and every little detail—the waves rolling in, the fishermen setting out to sea in their boats, the fishing nets ballooning in the breeze—is perfect. A film worth watching even if just for the sheer visual beauty of it.

What I didn’t like:

Perhaps, a few years ago, a younger I would have said that I found Chemmeen too tragic and too depressing. Today, I think I’m a little more mature. While I do think Chemmeen is tragic, the tragedy was not something I disliked, because I could see no other way for the film to move forward—anything else would not have had the impact, perhaps, that this story does.

A little bit of trivia:

TS Pillai’s original novel—Chemmeen—is part of the UNESCO’s Catalogue of Representative Works, a project to translate and disseminate global literature of a high calibre. The book has been translated into over thirty languages.

Perfect! Madhu, I’m impressed! Truly. For someone who is not a Malayali to get those little nuances, especially when watching a film with sub-titles is fantastic! Hats off to you!

LikeLike

(In expansion of my earlier comment) I know we all watch films with sub-titles (you have reviewed enough of them yourself), but I always wondered how much we understood. I used to wish I knew the language of the film I was watching just so I wouldn’t miss anything. Reading this review (of a film I have grown up with, an ethos with which I’m familiar), I’m totally awestruck at the little things you managed to take away without knowing either the language or the background (especially since I have no great hopes for the sub-titles!).

LikeLike

…and, in continuation to my reply to your previous comment: I don’t think I deserve the credit; that should go to TS Pillai and Ramu Kariat and all those others who made this film. I guess one reason why I was able to understand the nuances of it was that it was one of those very ‘universal’ sort of stories. Not something you’d need a lot of background to understand. This could have happened anywhere, in a somewhat traditional society, and where poverty can drive ambitious people to things they might otherwise not have done…

By the way. one question I did have: would you know why it’s titled Prawn? Of course, that’s one of the main things they harvest from the sea, but is there any symbolism attached to it?

LikeLike

Oh, didn’t see this question until now, Madhu. You know, I haven’t really thought about why the book might have been titled ‘Prawns’. :) Now that you asked the question, the only reason I can think of is that the story is set on a part of the coast where the catch is mainly prawns.

That area of the Kerala sea coast sees a very unusual phenomenon – at the onset of the monsoons, the prawns throng together, turning the sea red. In Malayalam, the phenomenon is called ‘chaakara’ – if you listen to the chorus of the song you mentioned (Puthen Valakkare) you’ll hear the word. It is incredible to watch,because one moment the sea is the greyish-blue that it usually is around the coast in the rains, and then suddenly, you can see it turning red before your eyes. Really, truly, red. As you may imagine, it is fantastic for the fisherfolk – all they have to do is to cast their nets and in a few moments, their boats are full.

LikeLike

*spoiler alert*

And perhaps, just the way the prawns throng up the sea to die, deliberately it might seem, the main leads also die – deliberately. Pareekutty and Karuthamma, definitely, and even Palani deliberately goes fishing in the night during the storm. (Ok, I’m reaching here… *grin*)

Also, I don’t know if you caught that part – Palani is supposed to be the child of the sea. He is blessed (which is also probably why he feels he can go into a raging sea and come back alive) by the sea mother, he tells Karuthamma once. So in fact, his death is because of Karuthamma’s fall from grace. Thus, the fable is true; if Karuthamma had not left that night to meet her lover, her husband would not have died.

LikeLike

Oh, I didn’t catch that part where Palani is supposed to be the child of the sea (there were sections of dialogue which weren’t subtitled, or where the subtitles went a little awry, so I didn’t know who was speaking what). But I think, if I recall correctly, he might have made that claim when Karuthamma first expressed her anxiety about him taking that boat out on his own.

That’s an interesting analogy between the leads’ deaths and that of the prawns. Who knows, you just might be right. :-)

LikeLike

Wow, Anu. Just reading your description of the chaakara gave me gooseflesh! That must be the sort of sight one can’t forget.

P.S. I was so enthralled by the idea that I went exploring Youtube to see if I could see a video of the phenomenon. Couldn’t find anything that actually showed the sea turning red, but there’s this one which shows the result of that – a huge catch. Not prawns, but still. The number of men having to pull that in is proof enough of how it must be. Fascinating.

LikeLike

Thank you, Anu. :-)

LikeLike

The only thing I would add is that Palani is considered to be one of the best fishermen on the coast. The reason why Chembankunju wants Karuthamma to marry Palani is because the latter is an orphan. (The wily father is hoping to save on the dowry by offering to have his son-in-law ‘share’ his business, and therefore increase his wealth. He has already destroyed Pareekutty.) The talk about Karuthamma begins because Palani is a rude and uncouth young man, and not very goodlooking to boot. So why should someone as beautiful (read ‘white’) as Karuthamma (ironic name there – Karuthamma means ‘the black one’; Sheela was paper white.) marry him unless she was flawed herself? And so the gossip begins – and Panchami, the younger sister is responsible for lighting the embers. (She is a pest, that one!)

LikeLike

Ah, okay. I didn’t get that bit about Palani being the best fisherman on the coast. I did understand that him being rootless could be the reason for Chembankunju being keen to get Karuthamma married to him, but that finer point about being able to save on a dowry – well, that missed me. Thanks for pointing it out!

That’s an interestingly ironic name for Sheela’s character – Sheela was definitely the fairest of everybody in the film, male or female. (So is the persistent ‘white = beautiful’ trope valid in Malayalam cinema as well? I had hoped not). :-(

Incidentally, while watching this, I realised that I’ve actually seen Madhu in a Hindi film – Saat Hindustani. He’s pretty out of his depth there (and in any case, it’s not a great film), but I liked him in Chemmeen.

LikeLike

It is strange, Madhu. (You force me to think about a whole lot of things that I hadn’t thought about before.) Is the white = beautiful trope alive in Malayalam cinema? Actually, I would say, not usually. Many of our very successful heroines have been dark-skinned. We have many, many songs celebrating the dark-skinned beauty. (One of the funniest was a song describing Shobhana as a ‘black beauty’ – the woman is definitely on the fairer side of the spectrum.) And because Kerala runs the gamut between the white-as-paper fair-skinned men and women to the black-as-pitch dark-skinned ones, I haven’t seen many movies or literature glorify ‘fair’ as a virtue.

Yet, in daily life, amongst my own relatives, I have heard the ‘Oh, she is so beautiful, so fair’, as if one automatically equals the other! (Or its corollary, which is even worse: She is quite beautiful; if only she had a bit more ‘colour’. Aaargh! That makes me want to kill someone!)

LikeLike

It’s interesting to see how people’s definitions of beauty differ – and often based on colour (which I don’t agree with, at all!) But I’m glad to know that cinema or literature in Kerala don’t glorify fairness as a virtue.

I remember an elderly relative saying (when I was 6 years old, and was taken to meet her after a couple of years), “Oh, she’s become fairer! Good, good.” Since my sister (who’s five years older than me) is very fair, this particular relative tended to din it into my head – at every opportunity – that poor, dark little me was terribly unpretty. Thank goodness, neither my parents nor my sister ever made me feel that way!

LikeLike

Ouch! Hugs to that little Madhu of many years ago! Thank heavens for your folks. And how I can relate! I spent an entire childhood being told I was the ugly duckling of the family; I’m sure it stung, though I don’t remember spending a lot of time bemoaning my lack of looks (selective memory, perhaps); but when I was 13 or 14, I remember my father telling me with a grin (we were at the railway station seeing someone off) that the ‘ugly ducking’ had turned into a rather goodlooking duck, even if not a swan. It was one of those moments that remain frozen in time. Dad and I always had the greatest relationships going, and I think, even then, even if I hadn’t internalised the ‘not pretty’ dichotomy (also add ‘too tomboyish’ *grin*), I think it eased the hurt that a child can feel.

LikeLike

Actually, the ‘unprettiness’ of me was only brought home to me at times like that, when an unfeeling relative or acquaintance would say something. The rest of the time, I was too busy enjoying my childhood (and squabbling with my sister!!) to remember. ;-)

I love that little anecdote about the good-looking duck. Sweet! *hugs*

LikeLike

I’ve not seen the film, but heard all about it. Why the director had to cast a “paper white” actress for Karuthamma’s role as you say?

LikeLike

(Answering instead of Dustedoff) Because, at the time, there weren’t any dark-skinned heroines in Malayalam. :) All the top heroines were rather fair.

LikeLike

I’d assumed the question was meant for you, Anu, since you were the one who’d made the comment about her being ‘paper white’. :-)

LikeLike

Hi, Madhulika.

I have ‘Chemmeen’ on DVD from Moser Baer. But as you mentioned, I found it tragic too. Maybe I need to watch it again to properly grasp it.

By the way, it ‘Chemmeen’ has been translated into English by Anita Nair (published by HarperCollins). I look forward to reading this translation as well.

LikeLike

And yes, the camerawork is wow!

LikeLike

Isn’t it? Simply superb. I kept looking at those gorgeous sunsets, with the fishing nets billowing and the waves coming in, and kept wanting to go to Kerala! :-)

LikeLike

Hansda, yes – I remember reading that Anita Nair had translated the book too. Must read that.

LikeLike

I did not see this movie ever. I am sure it was shown often enough on Doordarshan, but missed it for some reason or the other.

Your review describes the movie beautifully, Madhu. Thank you for the nice review.

LikeLike

Thank you, Ava! Unfortunately, back when I did watch Doordarshan (or any TV, for that matter), I don’t remember ever having seen any regional language films. So I have a lot of catching up to do! This was a good start. A very good one.

LikeLike

I’ve always believed that the films down South have amazing stories and narratives and beautiful performances. Your wonderful writeup proves so yet again. I just couldn’t stop reading… Wish they showed these films on TV. I remember way back Doordarshan used to air good regional films every Sunday afternoon. They should start once again.

LikeLike

Yes, I remember those Sunday afternoon regional language films too! But were they ever subtitled? Back then, there was such a paucity of things to watch, that I’m pretty sure I would have seen some regional films, but I don’t recall watching a single one.

LikeLike

Chemmen! A movie which brings back memories! I still remember the posters of this film plastered on the walls in Bombay. Not the big ones but the small ones. Regional films were often shown in Bombay as morning shows in the cinema halls. Chemmen used to feature quite prominently among them. If I remember right, the story was also published in form of comics.

I can’t remember though if I watched it on DD in the 80s. But it is nevertheless a real pity that I have lost nearly all contact to regional cinema now. In the 80s DD used to show regional films on Sunday afternoon and they were mostly all very good. Since I used to understand a bit of Kannada, I remember mostly Kannada films, particularly Ghattashraddha. Phaniamma left a deep impression on me at that time. Just wonderful!

I was also impressed by Malayalam cinema. Very moving stories and big dose of real life in them too!

Kerala means to me summer vacation. The last part of our 4-day train trip journey to your annual summer vacation would take us through the Kerala’s Malabar coast. After the scalding heat and dry parched earth of the Deccan plateau, the waterways of Kerala were a welcome change. *sigh*

See Madhu, you have opened a whole box of nostalgia with your Chemmen review!

Reading your review of Chemmen makes me really want to see it. I enjoyed the songs a lot! And such a poignant story with such human characters. Thanks for this wonderful review Madhu!

LikeLike

“Kerala means to me summer vacation.”

I envy you so, Harvey! I have never been to Kerala. :-( Somehow, we always end up doing road trips from Delhi, so we go to Himachal or Uttarakhand, occasionally to Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh. We’ve been toying with the idea of going down south for a holiday (I’ve been to Tamilnadu and Karnataka before, but my husband hasn’t), so perhaps we should begin with Kerala.

Chemmeen was a very satisfying film. If the other South Indian films I have lined up (and they’re an eclectic mix!) are even half as good, I’ll be a happy camper indeed. :-)

LikeLike

We are in India end-July to end-August. Want to make a Kerala trip then? :)

LikeLike

No, Anu, thanks. ;-)

And – guess why? We are finally going to Kerala!! Okay, for just four days, and not to too many places – just Kochi, and a couple of day trips from there. Down the backwaters, and to a bird sanctuary. We’re going in mid-May, which will probably be pretty humid, but that doesn’t matter. We’re both thoroughly chuffed about our trip. :-D

LikeLike

Thank you DO. What a fantastic review. It made for a wonderful read. The pictures look impressively shot indeed. I can just imagine the pleasure of watching this on a big screen.

As always, I search the net for any film that I found you liked and recommended.

I’ve found, but only in malyalam. :-(

The 100 year celebration is bringing up real gems. Looking forward to the next one.

LikeLike

Thank you, pacifist! Glad you enjoyed the review. It’s a lovely film, very sensitive and real. And the end is… well, haunting. No other word for it. I think you’ll like this film. Sadly, as you mention, the versions that can be found for online viewing don’t come with any subtitles (not that the subtitles in the DVD are great either, but still).

LikeLike

It does look stunning, and authentic, from the stills. Must watch it.

LikeLike

You must. It’s a work of art, really.

LikeLike

I grew up with Chemmeen. You see the novel was there on our book shelf (English translation). My parents had read it and had also seen the movie. My mum had the habit of narrating the stories of all the books she read and the movies she saw, of course I was all ears. I therefore grew up eager to experience the film and novel myself. I first read the novel and loved it and then saw the film, I think on DD. My memory of the film is not that vivid but I do not know that the novel held my attention right to the end.Wouldn’t mind seeing the film again, going by your screen caps it is quite apparent that the film has a picturesque backdrop. I saw it when colour television hadn’t come into the country. Greatr review Madhu— Shilpi

LikeLike

I have to admit, I’d not heard of Chemmeen till last year. Then, while I was reviewing Anita Nair’s book Cut Like Wound, I had a look at her biography and came across a mention of her having translated Chemmeen. Was reminded of that when I saw this film on Wikipedia’s list of films which have won the National Award for Best Feature Film.

It is a superb film, and the visuals are simply lovely. Do rewach if you get a chance, Shilpi – I think you’ll like it even more in colour!

LikeLike

I saw Chemmeen as child in Kerala amongst locales that were almost identical to those shown in the film. I loved the songs but I did appreciate the film more when I saw it much later at a Filmotsav in Bombay though I spent much of the time translating it to a Japanese reporter sitting next to me. I don’t remember if the film was shown with subtitles or if it had been whether the subtitling was atrocious. There are two memories that abide with me.

The first is towards the end of the wonderful song “Kaddalinakara ponno re ( Those who cross the seas)” sung by Yesudas, when the sun sinks from the blood red sky into the sea that will claim its blood.

The second is when Karuthamma’s fate is foretold in the old folk tale in this song. The lines are at 1:58. The music in this was a landmark for Malayalam cinema Salilda’s politics and his friendship with Vayalar, ONV Kurup and the IPTA drew him to Kerala and here he drew upon the wealth of folk music from Kerala and Bengal and mixed it with his appreciation for chordal harmonies, never heard in Indian classical music but always subtly present in folk. Salilda’s harmonies never left Kerala, he inspired a generation of music directors to experiment.

On the other hand it seems Thakazhi was less than thrilled with the film version of Chemmeen. He had written it bring realism into his works, to deal with the lives of the poor, the fisherfolk whose struggles had just begun, against casteism, mechanized fishing etc. The real character here is the sea, ever present seemingly immutable but ever changing, always the mother goddess bringing life and dealing death.

LikeLike

Thank you, SSW, for sharing all of that – the anecdote (did you get any nasty looks from people around while you were interpreting for the Japanese reporter? ;-)), as well as that bit about TS Pillai not much liking the cinematic adaptation of his book. Having never read the book, I did think the film’s story was centred round the sea and its power (yet its abundance), with the plight of the fisherfolk being highlighted only at certain times – for instance, when the monsoon comes and people end up borrowing money from Chacki. And, of course, at the end.

I’ve just been rewatching the two songs you posted. That frame with the setting sun is especially beautiful. It reminded me that when I was watching the film, I thought, “What I’d give to be able to see that for myself.” Lovely.

LikeLike

No nasty looks, discreet whisper’s were the order of the day. It was a very interactive filmotsav that I remember much hushed whisper’s abounded. At the same filmotsav when we watched Volker Schlondorff’s “Circle of Deceit”, everybody was whispering …”Wait , What. gasp…?”

That shot of the setting sun, you have to see it on the big screen. Even very large TV’s do not reproduce the immensity of it and the minuteness of you.

LikeLike

“That shot of the setting sun, you have to see it on the big screen.”

Someday, hopefully, they’ll show it at a film festival. Unfortunately, screenings of these old films has become so rare (or am I not looking at the newspaper listings closely enough?), that I doubt it’s going to happen in a hurry. Maybe I’ll spend my evenings on the seashore when I visit Kochi next month. :-)

LikeLike

This is a film which every Malayali watches at some point in his life for sure. I have watched it many times and still can’t get enough of it. Wonderful to have come across this review! I have seen the interview of TS Pillai on DD many years back, where he yielded answers in English and even now, Chemmeen is one novel every book lover in Malayalam would have surely read. Ramu Kariat’s next film was not a success though and he could never really make another one like this.

LikeLike

“This is a film which every Malayali watches at some point in his life for sure.”

I can imagine. :-) I’ve just returned from a trip to Kerala, and while on a backwaters cruise, happened to mention to our guide that I’d seen this film. And, of course, he knew what I was talking about. It is certainly a great film; I must get hold of the translated novel and read that sometime.

LikeLike

salil chaudary wants to bring hindi singers to malayam. It is because of him, kerala enjoyed malayalam lyrics in voice of lata and mannadey.

manna day sung manasa maine varu in chemeen.

Similarly Lata sung kadali chenkadali in film Nellu 1974

Both Mana day and Lata mangeshkar had bad accent. There was a hindi touch in both of their songs.

Asha bhosle also sung a song ‘swayamvara shybadina mangalangal’ in sujatha 1977.

asha perfecty sung the song even better than malayalam singers

LikeLike

Thanks a lot for this review. It helped me for my school project. Is there any chance i could get a review of tamil classic Thillana Mohanambal?

LikeLike

Thank you, glad you liked this. Sorry, can’t review Thillana Mohanambal, because I haven’t been able to get a subtitled copy of it.

LikeLike

Cheemeen is a very important film in the annals of entire Indian film industry. In particular, its story (by Thakazhi Pillai), cinematography (Marcus Bartley), editing (Hrishikesh Mukherjee) and music (Salil Choudhury) are truly of international standards. Even the acting is largely very good. And there of course is the natural beauty of Kerala, captured so very beautifully by Marcus Bartley’s camera and Ramu Kariat’s directorial eye.

Yet, as a film, I find its importance to be overstated in many regards- especially in regards to its cinematic language. Ramu Kariat’s direction, while being excellent, doesn’t quite have an original voice of its own, as Cheemeen very smartly, instead of borrowing from usual suspects like Ray, Ghatak, Sen, Roy, Dutt, Shantaram, Kapoor or Khan, does its referencing from films of other underrated (or rather underwritten) Indian film legends. The influence of Phani Majumdar’s Baadbaan, Rajen Tarafdar’s Ganga, Tapan Sinha’s Hansuli Banker Upakatha & B. Sanyal & S. Guha Thakurta’s Dheur Parey Dheu is quite evidently on display in Cheemeen, thus robbing it off its tremendous distinctiveness, unlike the novel, which is a monumental achievement in original Indian writing.

When, I first read the novel, I was simply astonished by T. Pillai’s gorgeously beautiful and distinct style of writing. I instantly remember going that here’s a writer with an original and impressive voice, whose importance should be rightfully placed alongwith the likes of Tagore, Premchand, Bankim, Sarat or Tarashankar. Alas, the film doesn’t quite evoke the same admiration as the novel does, even though the film is wonderful, because of the above mentioned reasons.

That being said, Cheemeen primary importance lies in the fact that just like Do Bigha Zameen in Hindi before, it made it possible that a realistic and artistic hit film of international merit can be made in South, all the while retaining the traditional characteristics of popular Indian cinema like songs and melodrama. If not for Cheemeen, one would not have seen the excellence that today one sees in Malayalam film industry. And therein lies the abiding influence, relevance and importance of Cheemeen in Indian cinema.

LikeLike