If, like me, you were old enough to be watching films in 2000—and you watched Hollywood films—you might have come across the Brendan Fraser-Elizabeth Hurley comedy Bedazzled. It was about a geeky, socially inept but otherwise sweet fellow (Fraser) who makes a pact with the Devil (Hurley), who promises to grant him seven wishes in return for his soul. Unfortunately for our hero, all his wishes come to nought, leaving him even more distressed than he was originally. It was a funny film, and Brendan Fraser, in my opinion, shone as a comic actor.

I discovered, a few weeks ago, that the 2000 Bedazzled, directed by Harold Ramis, was actually a remake of a 1967 British film of the same name. Directed by Stanley Donen, Bedazzled was based on a story by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, who also acted as the leads in the film: Dudley as Stanley Moon, Peter as the Devil.

The story begins in a church, where Stanley is praying very hard that God give him a sign. Something to assure a despondent Stanley that there is someone listening.

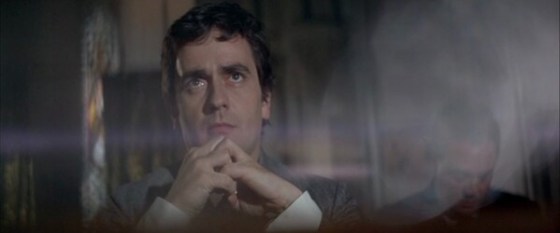

Not God, but someone (Peter Cook) is. Listening, and looking, watching Stanley very carefully.

Stanley’s main problem is his inability to speak his mind (and more importantly his heart) to the girl he loves, Margaret Spencer (Eleanor Bron). Margaret works as the waitress in the Wimpy’s where Stanley is the short order cook, and though all she ever says to Stanley are orders, they’re music to his ears. He’s too tongue-tied to tell Margaret how he feels…

… and just when he’s managed to screw up the courage to say something, he sees Margaret get into a car with another man, and go off laughing happily. Stanley is so heartbroken, he goes home and tries to hang himself. His luck being what it is, the water pipe around which Stanley has tied the noose gets wrenched out by his weight and there’s water spewing out—when in comes a stranger.

After some initial chitchat (Stanley, unsurprisingly, is befuddled: who is this man? And then annoyed: why is he so bossy?), the newcomer introduces himself as the Devil. Stanley is of course disbelieving, and the Devil, to help him believe, offers Stanley a wish. I will grant it, whatever you want (no, not Margaret).

Stanley settles for a particular ice lolly.

Which the Devil buys for him from an ice cream stall, and because he doesn’t have change, Stanley is obliged to shell out six pence for the treat. Stanley isn’t convinced by this particular feat, of course, and the Devil finally proves his chops by whizzing the two of them from one part of London to another. Stanley, whose ice lolly has completely evaporated in the process, is finally convinced.

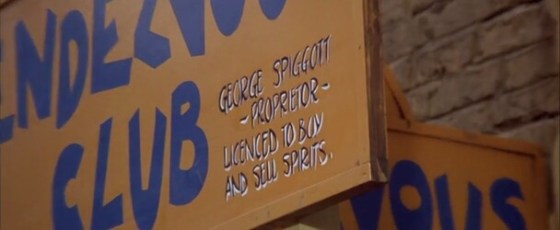

The Devil—whose name, by the way, is George Spiggott, and who has his office nearby—takes Stanley there.

Inside, as bouncer, there’s Anger (Robert Russell), who unleashes his rage on Stanley and tosses him out before the Devil can rein him (Anger) in. The Devil discusses his proposition with Stanley: he’ll grant seven wishes in exchange for Stanley’s soul. After all, Stanley hardly even realizes he’s got a soul; he won’t miss it. And removing Stanley’s soul is going to be an absolutely painless process; it will be just fine. When Stanley finally agrees, the Devil whips out a contract, has it signed by a witness (Sloth, who is his inhouse lawyer), and once Stanley has signed too, they’ve got a deal.

Stanley’s first wish is that he be more articulate. Since Stanley anyway finds it so difficult to say what he wants, it’s the Devil who has to end up putting into words what Stanley’s wish might be. That he come across as an intellectual; that he be able to talk intelligently and articulately enough to impress Margaret.

Hey presto, Stanley finds himself with Margaret, walking through the zoo and talking. Talking intelligently. Talking articulately. And talking, and talking. They get on to a bus, Margaret getting no chance to get a word in edgeways. They arrive at Stanley’s home, and he’s still jabbering away. Fortunately for this suddenly overly articulate Stanley, Margaret seems to be very happy to hear him go on and on.

They have a drink, she looks around at the décor of his home, and the conversation becomes rapidly more suggestive as Margaret fondles an artefact; as they talk about the way people should be allowed to touch each other whenever they want to, and so on…

Stanley is getting increasingly restive, hanging on every word of what seems like a very permissive young woman. Finally, when he can’t hold on any more, Stanley leaps on Margaret, sure that she’s going to reciprocate.

But Margaret starts to scream, and alarm bells go off, and through a haze of frustration and bewilderment, Stanley can hear the siren of a police car approaching.

He quickly blows a raspberry—according to the Devil’s instructions for getting out of a situation brought on by a granted wish—and all’s well. The next moment, he’s out of the mess and pottering quietly along beside his companion, the Devil instructing pigeons to swoop over so and so walking below, spattering them with pigeon shit.

Stanley is indignant about what happened, but the Devil (“Call me George,” he tells Stanley) brushes it off. This will happen; there’s a difference between what people say and what people do. Margaret may have sounded permissive, but that’s it. It doesn’t mean anything more. Wouldn’t it be far better if Stanley wished for Margaret to be married to him? And he wealthy and powerful, rolling in money? Yes, yes, yes, says Stanley. Also, for Margaret to be very physical.

And here he is, tycoon Stanley coming home (in a Rolls) to a grand big manor. The signs of wealth are all around: the huge mansion, the butler, the rolling lawns around, the friends playing croquet on the lawn. There’s even the physical Margaret, who—to Stanley’s horror—is getting very physical right now with a fellow named Randolph (whom Margaret is going on calling Randy in a very obvious sort of way).

Randy is Margaret’s harp teacher, but (as Stanley agrees with a friend—who looks exactly like George Spiggott) he and Margaret seem to spend their time learning other things. This isn’t just a single instance of what might perhaps be overfriendliness on Margaret’s part or a misunderstanding on Stanley’s; it’s quite clearly the norm. The physicality of Margaret that Stanley had wished for is very much there, only it’s not for him.

And thus it goes on. In between pulling pranks on other unsuspecting souls, George grants Stanley’s wishes to help him get Margaret. All the wishes, of course, end up being literal translations, so to say, of what Stanley asks for. George is good at finding the loophole in each wish uttered, and twisting it around so that what Stanley gets is really not what he wants at all.

All the time, too, while Stanley is hanging out with George, Margaret has been summoned to Stanley’s ramshackle little home, where the noose around the waterpipe has been found, along with a suicide note addressed to Margaret. There is no trace of any body, so Margaret and the police set out to find Stanley: by dragging the river, for example; and checking out the inhabitants of the morgue.

Surely this means she feels something for him, wonders Stanley? She’s concerned, she does say that he was a good sort, putting so much concentration and effort into flipping burgers… surely she reciprocates?

All the while, also, George is working towards an objective of his own. He has a pact with God: if he, George, is able to win 100 billion souls, he has a chance at being elevated to an angel again.

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore based this story on the classic story of Johann Georg Faust, who was supposed to have sold his soul to the Devil in return for unlimited knowledge and power. According to this article, Faust (who was a real person), ended up immortalized because of a book, published in 1587 (after his lifetime) and written by an anonymous writer: Faustbuch, as it was named, consisted of stories about Faust that were ‘narrated crudely and were further debased with clodhopping humour at the expense of Faust’s dupes.’

I haven’t read Faustbuch and am unlikely to, but that description sounds a lot like Moore and Cook’s version of the Faust legend. No, Stanley Moon has no desire for knowledge and power—unless it’s knowledge to impress Margaret Spencer and power over her—but the way the Devil dupes him, again and again, is very familiar. As is the ‘clodhopping humour’.

What I liked about this film:

The overall plot, of a rather naïve man who is taken for a ride by the Devil and whose every wish is turned hilariously on its head, leaving him worse off than before. It’s an amusing premise, and the little nuances to it—the loopholes the Devil finds in Stanley’s wishes, the fairly juvenile pranks the Devil pulls on other people by way of ‘spreading evil’ in the world, and the occasional props that one sees in the film contribute to the humour of it. For props, have a look at these delightful examples. The signboard outside George’s office is one:

And the T-shirt Anger wears is another:

And, Dudley Moore’s acting. As poor put-upon Stanley Moon, he’s very funny: the sort of man one can imagine making a deal with the Devil out of desperation. Peter Cook is good, too, but Moore takes the prize here.

Finally, I liked the subtly satirical comments on God, on religion, and on the state of the world. I wouldn’t really have expected this depth from Bedazzled (which was pretty shallow in most places!), but it was there, and it was surprising.

What I didn’t like:

The seven deadly sins. Yes, I can see that it would fit in with the whole idea of the Devil, and the sins working with him, for him. But after a while, they get quite predictable and a little forced. Raquel Welch as Lillian Lust seemed to me the main reason why these would be bunged in: she would have been, I suppose, the oomph factor here. Personally, I don’t like her.

The whole Welch-as-Lust thing is actually connected to another problem I had with this film, of a certain level of objectification of women. Margaret as Stanley’s lodestar, as the woman he idolizes and wants so much to impress, is all very well; but I found the situations Margaret finds herself in problematic. For instance, there’s a cop getting fresh with her while she’s accompanying him trying to find out what happened to Stanley (and Margaret does nothing about it).

Plus, there’s some slapstick—for instance, in the episode where Stanley ends up in a convent—that had me rolling my eyes, it was so juvenile.

But, as importantly:

The comparison.

How does this Bedazzled compare to the 2000 Bedazzled, starring Brendan Fraser and Elizabeth Hurley?

Superficially, the story is pretty much the same. Brendan Fraser plays a geek named Elliot Richards, who is socially very inept (he is constantly the butt of jokes in office, and seems, most of the time, to not even realize how much of a misfit he is). Elliot is in love with a colleague named Alison (Frances O’Connor), who barely even knows Elliot exists; and when the Devil (Hurley) introduces herself and her proposition (seven wishes = Elliot’s soul), Elliot’s first thought is to be married to Alison. As the story plays out, one wish after another, it emerges that the Devil is basically finding loopholes to make life miserable for Elliot and not really give him what he wants.

The very first episode, where Elliot wishes he were rich, powerful and married to Alison, is similar to Stanley’s wish—and exploits the same loophole: she is married to him, but in love with another. It plays out differently, though, and the other episodes too aren’t exactly the same. The suave and articulate Elliot/Stanley, the hugely successful Elliot/Stanley with hordes of screaming fans surrounding him: these are there, but what form he (and his situation) takes is different, and how that is a big zero when it comes to his relationship with Alison/Margaret… is quite different.

Also different is the Devil. Of course, in the very fact that this is a woman. But also in that (though she does mention the seven sins in passing) all that convoluted and rather pointless meandering with Lust, Sloth, Anger etc is missing in the 2000 film. In addition, the interludes, in which our beleaguered hero has a chat with the Devil and expresses his next wish, are far shorter in the later film.

All in all, the 2000 film is crisper, more taut, less flabby. The extra bits, which make the 1967 film a little meandering and detract from the main plot, have been neatly chiselled out, making the film more focussed on its inept lead’s miseries (and tragedies). Plus, I personally like the leads better: I think Fraser’s a much funnier actor than Dudley Moore, and Elizabeth Hurley makes for a more wicked Devil than does Peter Cook (she looks like she’s having a whole lot of fun playing the Devil, too). Also—perhaps a sign of a world that has moved on from the 1960s?—the 2000 Bedazzled doesn’t objectify women. Not just in the sense that it has a woman play the Devil, but also in the way Alison is portrayed: this is a woman with agency, a woman who controls her own life.

So, yes: if you (like me) enjoy the 2000 Bedazzled, I would actually caution you against watching its original. The remake is better.

P.S. The 2000 film has one nod (at least) to its precursor. In one scene, the Devil appears with two dogs, which she’s out walking. They are straining at the leash, and she shouts at them to stop defying her: the dogs’ names are Peter and Dudley. Heh.

Madhu,

I am happy with your conclusion that the remake is better than the original, because the remake is accessible, several English movie channels carry it regularly, and I have been passing it buy. Now I have added it to my watchlist.THe personification of emotions is an interesting concept, because a recent film <i>Inside Out 2</i>, running in theatres, has this theme. AK

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hadn’t heard of Inside Out 2. Thanks for telling me about it, AK.

Actually, even the original Bedazzled is readily accessible – and for free. It’s on Archive.org. But really not worth seeing, unless as academic interest if you want to compare it to the later Bedazzled.

LikeLike

Hmm… this sounds interesting; the remake, I mean. I’m tired of women being objectified, and I much prefer Brendan Fraser to Dudley Moore anyway. And having Elizabeth Hurley as the Devil is just the bait to reel me in.

Thanks, Madhu.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading, Anu. Seeing the way women are made out to be nothing more than sex objects really put me off the 1967 movie. :-( And even worse, that it’s supposed to be funny. Ugh.

LikeLike