In the original Japanese, Ten to Sen. The English title is also often translated as Points and Lines, which was how I originally saw it being referred to.

In a cinema that—at least to the outside eye—seems to be dominated by the works of directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu, films that are rather more ‘pure entertainment’ tend to get overlooked. The amusing yet insightful little look at childhood, Ohayo (1959), for example; or this classic noir, a police procedural that revolves around trains: their schedules, their stations, their networks… and how they (along with a ferry and various aeroplane routes) might have been instrumental in helping a murderer pull off a crime.

The story begins on a bleak and deserted seashore, where two dead bodies have been found. The cops from the Fukuoka Police Department have come to investigate, and seem to have reached a consensus that this is a case of a double suicide: everything points to it. A man and a woman, her head sweetly pillowed on his arm, lying stretched out beside each other. The police doctor comes to the conclusion that they’ve died of cyanide poisoning.

One of the police officers doesn’t agree with the conclusion that this is a suicide. Toriumi (Yoshi Kato) is sceptical that these two came here to put an end to their lives. When people in love commit suicide like this, together, they prefer to do so in scenic surroundings; why would anybody come to a sad-looking dump like this, to make it the last thing their eyes see? [I don’t agree, but anyway].

Toriumi’s colleagues don’t agree with him either: he mostly gets laughed at, but they begin their investigations anyway. The identities of the dead people are quickly ascertained. The man was Sayama Kenichi and he was a government official, working in the Department of Industry, as an Assistant Section Chief in the Investigation Section of the Business Division. The woman was Toki, a hostess at a Tokyo restaurant.

Toriumi’s boss has sent out a detective to make some more enquiries, and it’s discovered that Sayama had arrived at the seaside town by himself on October 14th; he had rented a room at an inn and seemed to be waiting there for someone. On October 20th, at night, he received a call from a woman and left the inn after that—only to be found dead the next morning.

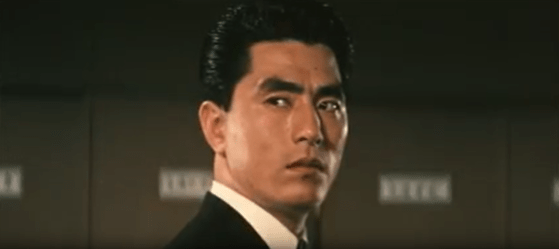

Perhaps because Sayama was a government employee, and that too not a nobody, an officer of the Metropolitan Police Department is deputed to investigate the case. Mihara (Hiroshi Minami) is young and earnest, and it doesn’t take long for him to buy in to Toriumi’s contention that this was no suicide.

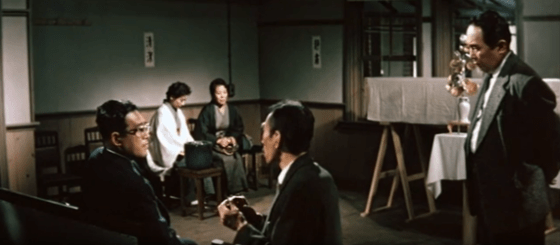

In the meantime, too, the bodies have been claimed by their friends and relatives, and both parties are present at the same time in the police station. Sayama’s brother, and two women, one a colleague of Toki’s, the other an older woman who might be Toki’s mother. Instead of commiserating with each other, the two parties are at daggers drawn. Sayama’s brother, in particular, is furious: how could his brother have been having an affair with a lowly hostess? She must have driven him to suicide; she killed him.

He is so brutal that the older woman gets very distressed and starts crying. When she’s calmed down and Toki’s colleague is more composed, Toriumi and his boss question her. She admits that while the women working at the restaurant had known that Toki had a boyfriend, they didn’t know who he was. But then, on October 14th, they had seen Toki at Tokyo train station with the man—with Sayama, as the woman now knows him to be.

The woman explains how it happened: she and her colleague were standing on one platform; there was no train at the platform, or even at the next platform. So, just briefly, across the tracks, the two women had a clear view of a couple walking along on the platform opposite them. Toki and the man, climbing into a train: the express to Hakata.

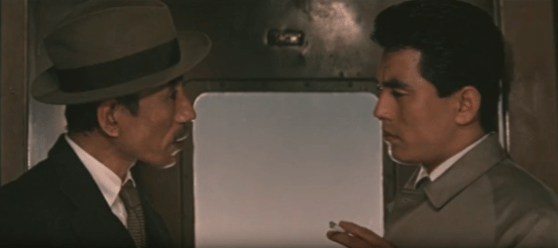

Toriumi reports all of this to Mihara, and adds that they—Toriumi’s team—had discovered, among Sayama’s things, a lone ticket to the dining car on the Hakata train. Why would Sayama have dined alone if he was travelling with Toki? Toriumi’s assertion is that women never say no to food [another of his illogical and pointless assertions], so if Toki had been on the train, she would certainly have accompanied Sayama to the dining car. Ergo, it can only mean that Toki got off the train sometime before Sayama went to eat.

Toriuimi and Mihara get to the scene of the crime and ask around among witnesses whom Toriumi has already questioned. These are people who had spotted Sayama and Toki on the night of October 20th. One man, a fruit seller, remembers them walking past his shop; another man, who happened to be drunk that evening, recalls them overtaking him and remembers the woman remarking to her companion about what a dreary and bleak town this was.

When they get back from this trip, Mihara reports to his boss, Kasai (Takashi Shimura) who brings up the point that in all their investigations, the police have not been able to find any evidence that Sayama and Toki were having an affair. Not one love letter, nothing. The only proof of their relationship, such as it is, is the testimony of Toki’s colleagues, who saw her on the platform with Sayama.

This needs to be investigated further, so Mihara goes once again to question the hostesses who talked to him. He takes them out for a meal, and suitably softened, they reveal that it wasn’t of their own accord that they’d spotted Toki and Sayama. Someone pointed them out.

This man, Tatsuo Yasuda (Isao Yamagata) is a customer of the restaurant, in fact Toki’s customer. He’s an engineer, and therefore a VIP at the restaurant. On October 13th, he’d been dining at the restaurant and had then invited these two hostesses to dine with him the following evening. It was at this dinner that he’d asked if, after dinner, they could give him a lift to Tokyo Station.

Thus it had been that they had accompanied him to Tokyo Station, where he had pointed out Toki and Sayama.

Mihara goes to meet Yasuda. Yasuda seems willing enough to co-operate. When asked for his whereabouts on October 20th and 21st, he explains that he was travelling on business to Sapporo, and readily offers exact dates, times, flight details, and so on. Mihara makes a note of all of this. On being questioned, Yasuda also gives the information that he is married; his wife Ryoko (Mieko Takamine) is an invalid: a bad heart keeps her pretty much confined to her home. She therefore lives on her own in another town with a maid to look after her, and Yasuda travels every weekend to visit her.

Mihara is already beginning to smell a rat. Now he goes to meet Ryoko, and finds himself feeling even more certain that something is definitely wrong here, and Yasuda had a hand in the deaths of Toki and Sayama. But why, and how? If Sayama and Toki were in Fukuoka on the night of October 21st, and Yasuda was in Sapporo on the same night, how could he have murdered them?

After all, it all boils down to points and lines.

Point and Line was based on a novel by Japanese crime writer Seicho Matsumoto, a book that has been described by J Madison Davis in World Literature Today as one of the ten greatest crime novels ever. Although I’ve seen it written that the film, directed by Tsuneo Kobayashi, is a fairly faithful copy of the book, I cannot comment on this, since I’ve not read it. I have, however, read Matsumoto’s excellent Inspector Imanishi Investigates, so I can well imagine that Point and Line might be a good book.

As for the film itself:

What I liked (and what I didn’t):

I appreciated the interesting insights the film offers into themes in modern (as in 1950s, post-war) Japanese society. The corruption, the stifling sense of hierarchy which meant (means? even now?) that a subordinate was obliged to do any and every thing a boss demanded, no matter what. The position of women.

The position of women, though rather subtly revealed in the character of Yasuda’s wife Ryoko, is a case in point. This is a woman who is very beautiful (I have to admit I didn’t think so, but it’s an opinion that is voiced repeatedly by various characters in the film). Also obviously educated, wealthy, used to a certain status—and yet, her sense of insecurity is immense enough to drive her to plead with her husband for a kiss; to go along with whatever he demands; even to let him have extramarital affairs just so he is happy. It’s disturbing, but also, I realized, not just a Japanese thing, not just a 1950s thing. This buckling under the weight of patriarchy, this giving in to pleasing a man simply because he is a man… no, it’s by no means an isolated practice or a dead-and-gone one.

The crime and its investigation are interesting, but I have to admit that the crisscross of trains and planes did confuse me quite a lot. By the time Mihara and Toriumi had solved the crime, I was just about able to figure out how and why Sayama and Toki were killed—the nuances of it had gotten all muddled.

Still, though, a good film: a solid example of the police procedural, and worth a watch.

A copy of the film, with English subtitles, can be viewed at ok.ru, here.

Sounds very interesting. And a bit like Parwana – no, not the story, but the plot device of using various trains and other transport to commit a murder, successfully.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Anu, I had completely forgotten about Parwana! But now that you mention it, yes: it does bear that similarity to this film. I must rewatch it sometime, I remember enjoying it a good deal (and, of course, being surprised that AB played the villain – I kept thinking till the end that there would be a catch and it would emerge that he really wasn’t whom he’d been set up to be. Of course on reflection I had to admit that he was still too new in his career to be established as the eternal hero. ;-))

LikeLike

Sounds very interesting and promising. But as you have said, the whole details will confuse me and muddle up things in my mind and it is very unsatisfactory not to know how the plot works.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It might well be my fault! Perhaps I wasn’t paying close enough attention. ;-)

LikeLike

Quite intriguing. Certainly the kind of movie right up my alley. I will put it on my list and wait until it’s available on physical media or on a legit streaming site.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Given that you’re also a reader, the book might be easier to get hold of – I think the film (old Japanese, but not one of the more popular old directors) isn’t one of the type streaming services would generally offer. The book, however, is available (I haven’t read it, though).

LikeLike