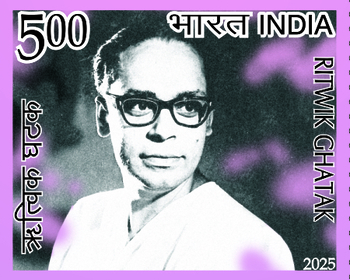

Today is the 100th birth anniversary of one of India’s greatest film directors, Ritwik Ghatak: he was born in Dhaka on November 4, 1925.

I have to confess I’ve not seen very much of Ghatak’s work, mostly from an innate tendency to shrink from ‘sad movies’. I did watch Meghe Dhaka Taara some years back (and admired it, though it was, as expected, tragic). For his birth centenary, I wanted to review another of his films, and this one popped up in the searches. It immediately drew my attention, for several reasons. For one, it stars Madhabi Mukherjee, one of my favourite actresses. For another, it also starred Abhi Bhattacharya, a familiar face from Hindi cinema, and one I’ve always liked. At least, I reasoned, if I had to watch a sad film (at a time when I’m so busy and stressed, I’d rather watch mindless fluff)… at least there would be people onscreen I enjoy watching.

The story begins in a refugee camp. It is 1948, and Haraprasad (Bijon Bhattacharya) has established a tiny school for the children of the camp; he hoists the national flag and makes an announcement. He will teach Sanskrit and Bangla; and Ishwar Chakraborty (Abhi Bhattacharya) will teach English and History.

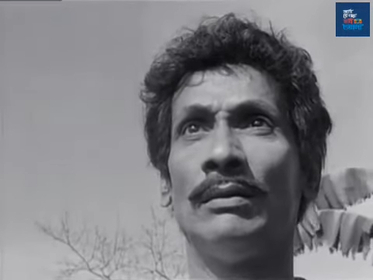

In another part of the camp, a poor woman is looking for shelter. She tells a man, who wants to know more, that she and her son Abhiram (Tarun) are low-caste, from Dhaka. The man scoffs at her and tells her to get along; this place is not for refugees from Dhaka.

Just afterwards, a lorry draws up and people are willy-nilly shoved into it. In all the hubbub, Abhiram gets separated from his mother and she is taken away in the lorry, still screaming and wailing for her son. Abhiram is too young to know exactly what has happened or what he should now do (he is, actually, too young even to know that he is low-caste).

Fortunately for Abhiram, Ishwar Chakraborty takes him under his wing. Ishwar has a younger sister named Sita (Indrani Chowdhary), who soon makes friends with Abhiram.

Shortly after, too, Ishwar runs into an old acquaintance, a man named Rambilas (Pitambar), who had been in college with him. Rambilas is wealthy, and tells Ishwar that he owns a rice mill and a foundry in a village named Chhatimpur, near Ghatshila. He remembers Ishwar as being a conscientious, dependable sort; and now, having heard of Ishwar’s less-than-enviable financial situation, he offers Ishwar a job at the factory.

Haraprasad is angry when Ishwar tells him of his decision to take the job. Haraprasad feels Ishwar is betraying him, betraying the cause. But Ishwar is determined, and sets off with Sita and Abhiram towards their new home in Chhatimpur.

At the railway station, they are met by Mr Mukherjee (Jahar Roy), who is the foreman at the foundry. Mukherjee escorts them to the house, which is on the bank of the Subarnarekha River. Even as they walk to the place, a seemingly mundane but eventually significant thing happens.

Mukherjee, chatting with Sita, tries to beguile the child by telling her of the wonderful new home beside the river. The birds, the flowers, the butterflies. The large house, full of music and singing. Ishwar, incensed, tells Mukherjee he shouldn’t lie to children.

Later, once they’ve arrived and Ishwar has begun work, Mukherjee introduces him to the manager of the mill, the man who is going to be Ishwar’s boss. In name, at least; he has lost his mind. Mukherjee tells Ishwar that the manager’s daughter ran off with some man, and ever since the manager’s lost his wits too.

Anyhow, Ishwar, Sita and Abhiram settle down in their new home. Soon, Ishwar has found a music teacher for Sita, and she is learning how to sing. Her teacher is very pleased with her progress; he intends to teach her classical songs as well.

All is happy and well. Abhiram and Sita go out to play while Ishwar is away at the mill. They wander about among the ruins and debris that dot the countryside: the airstrip, the shattered plane—downed during World War II—nearby. The British clubhouse, now only its half-collapsed walls standing. They spend their time clambering over all of this, walking beside the Subarnarekha, enjoying each other’s company…

Not for long. Abhiram must be educated, and there are no schools (or no good schools?) around Chhatimpur. Ishwar manages to get admission for him into a boarding school far away, and Abhiram leaves. But he will return, every year, to be with his adopted family.

And when he comes back, now all grown up (Satindra Bhattacharya), Abhiram and Sita (now Madhabi Mukherjee) shyly acknowledge their love for each other. They will get married, is the unspoken agreement.

But one day Rambilas, the owner of the mill and therefore Ishwar’s ultimate boss, comes visiting along with his wife. The manager of the mill has finally gone so mad, he cannot be retained at the mill any more, and Rambilas has it in mind to have Ishwar take over. This visit acts to help him get acquainted, somewhat, with Ishwar’s household—and he is disapproving of Ishwar’s having adopted, even if informally, Abhiram. Who knows which caste the boy is from?

Later, once Rambilas has gone, Mukherjee tells Ishwar that he (Rambilas) is a very conservative sort (in other words, caste-conscious); Ishwar might do well to remember that. If Ishwar hopes to progress in this job, he cannot afford to do anything Rambilas might disapprove of.

We, of course, know that Abhiram is actually from a low caste. But will he, and the others—especially the very prejudiced Rambilas—find out? If and when they do, what will be the repercussions?

Subarnarekha’s title appears in English as ‘The Golden Thread’ (I would probably have translated this more literally as ‘The Golden Line’), but it made me wonder: was that really what Ghatak meant? Was the reference in the title to the river, and the river only? If ‘The Golden Thread’, then what thread (or line, if I may add my two bits) would that refer to? The line that demarcates? Rich from poor, high-caste from low, privileged from subaltern, man from woman? The lines in Subarnarekha are not always clearly etched; sometimes they’re there, but so faint we cannot see them until something happens that brings them into sharp relief, reminding us that divisions exist, even when we try to ignore them.

What I liked about this film:

The overall theme, the entire package, so to say. No, it’s not happy. There are moments of sweetness and joy, but eventually, it is more a story of struggle and despair, of trying desperately to attain contentment and happiness—but the way it all comes together is unforgettable. There was nothing about this film I didn’t like. Even the sadness of it all. And yes, it was sad; it was heartbreaking, especially in two important sections when Ghatak really builds up the sense of doom. In both cases, the characters are going about their everyday lives, without the faintest whiff of anything ominous. In fact, in both cases too, they are looking forward to coming happiness; there is hope, there is the promise that things will be better. Yet, in both cases, too, something else is happening alongside, something which, even as I watched, made the alarm bells start ringing in my head.

This, by the way, made me marvel at the way the script (also by Ghatak) had been written: what a superb handling of the audience’s emotion, allowing us, the viewers, to look on helplessly as these characters we root for have not a suspicion that their lives are just going to be turned upside-down.

Of course making the audience privy to secrets yet hidden from the characters is nothing new; but my point here is to highlight the script. The realism of it, the nuanced depiction of emotion, of human nature and its many foibles. The prejudices we harbour, whether they be the more visible type like casteism, or those more often disguised as a beneficial stricture (a patriarchal notion, for instance, of what the ‘woman of a house’ may do to earn an income, when driven to it). The dilemmas we must grapple with. Our relationships, our insecurities, our ambitions (and where they clash with the hopes and dreams of those we love).

One of the more striking aspects of the plot is the cyclical nature of it: something (a character, an idea, even a remark) comes in near the beginning, and then, much later, the story comes full circle. And it always, in the process, makes a telling comment without outright saying so.

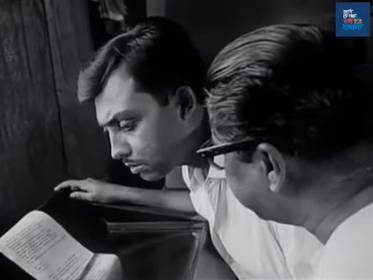

For example, among the first scenes is one set in a newspaper office, where a young reporter has just come in: it’s his first day, and he’s eager, earnest, ‘good’. So much so that when the news arrives that Gandhiji has been assassinated, the man breaks down and cries.

Near the end of the film, years later, the scene circles back to the same office, the same reporter, the same boss. The reporter is now a jaded man, cynical and indifferent. A man who, when faced with the news of a death, is able to not just retain his composure but, sadly, not let it affect him at all.

(Interestingly, this reporter, his office, and everything connected to him, is restricted to these two scenes).

Ghatak does a brilliant job of it, and—as director—of bringing it all to life subtly and sensitively onscreen.

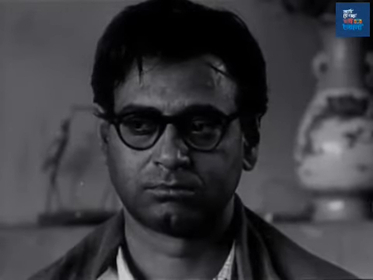

Then, there’s the acting. The cast is excellent, but for me, two people stood out: Madhabi Mukherjee and Abhi Bhattacharya. Neither of them speaks a lot; both Sita and Ishwar are relatively quiet—but their eyes, their expressions, speak volumes.

While on the topic of these two actors, I have to comment on how convincingly people in this film are shown to grow older. Madhabi Mukherjee, Abhi Bhattacharya, and Satindra Bhattacharya are all shown as adults and older adults. People, too, whose looks bear the brunt of the stress of passing years. Rarely have I seen, in Indian cinema, a combination of make-up (by Manotosh Roy) and acting that did not look forced or obvious.

There is, too, the music, composed by Ustad Bahadur Khan. The beautiful, repeated Aaji dhaner khete rudra-chhayar lokuchuri khele is lovely (and poignant). And, since Sita is trained in classical music too, there are several instances of her singing in Hindustani (Arati Mukherjee sings for Madhabi Mukherjee, and is exquisite). The most prominent one, repeated a couple of times is Dekho bhor bhayi (‘Look, the dawn has come’—what a fitting song for this film, at the same time both sadly ironic and eventually appropriate too).

Last (but not least), the Subarnarekha itself. The film has some stunning scenes along the riverbank, with some of its most crucial moments on the sands of the bank. The slow-moving, sluggish waters; the fishermen throwing out their nets; the boulders along the banks; the sands, drifting deep in place: Ghatak made this a tribute to the river, too.

Thank you for the cinema, Mr Ghatak. May it live on.

There are several copies of Subarnarekha, with English subtitles, online on YouTube. The Shemaroo one has the cleanest video, but it does have some crucial scenes missing near the beginning. I watched this version, on Rajshri Bengali, for the initial fifteen minutes or so, and then switched to Shemaroo.

May I say at the outset that this is one of your best-written reviews? Quite possibly the best (I’m casting my mind back to some of your absolutely scintillating ones). And that’s saying something, given the high quality of your writing.

Subarnarekha was a film I watched while I was still in college. The college film club folks had a Ghatak retrospective, and this was the time I watched anything on film. Some scenes have still stayed with me… especially the one where Sita meets the bahuroopi.

I’m not in a frame of mind to revisit Ghatak, but this review brought it all back to mind. Thank you for that.

LikeLiked by 2 people

this is one of your best-written reviews

Anu, you have made my day. Coming from someone who writes as incisively and brilliantly as you do, that is high praise. Thank you so much.

The scene where Sita meets the bahuroopi is indeed memorable, isn’t it? Even the space where it happens – that deserted old airstrip – is so atmospheric.

Yes, not a film one would want to see to relax, but such a good film!

LikeLike

Beautiful review. Thank you for bringing this film into my awareness. One day when I have the bandwidth for it, I will watch it and then revisit this review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Ritika. And yes, do come back and tell me what you thought of the film once you’ve seen it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reviewing this film, Madhu. I echo Anu in saying that your review is very well written and your observations are spot on. This is one of my favorite Ritwik films although I confess I haven’t seen it in a while. Must re-visit it soon. Watch Ajantrik if you haven’t already.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Soumya, for your kind words. I am so glad you liked this review. As for Ajantrik, no; I haven’t watched it, but will put it on my list right now. Thanks for the recommendation!

LikeLike

Reading your review, dear Madhu, made me feel as if I watched the whole movie. Thanks for that.

Lots of stuff going on, thus keeping my comment short.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope it’s just that you’re very busy, Harvey, and that all is otherwise well. Take care, and thank you for reading.

LikeLike