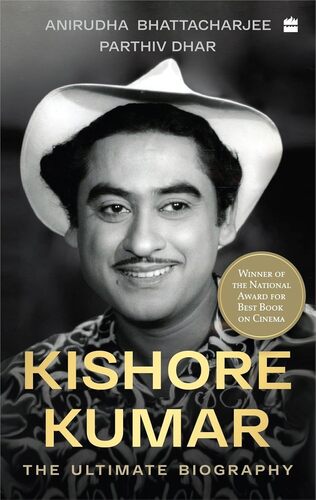

Anirudha Bhattacharjee—who has gifted me quite a few of his books on Hindi cinema in the past—sent me this book last year. I accepted his offer of the book for two reasons. For one, there isn’t a book by Anirudha that I have not enjoyed. For another, I really like Kishore Kumar the singer.

Note that disclaimer: the singer. When it comes to Kishore the actor, I’m not so sure. While I find him quite enjoyable in films like Pyaar Kiye Jaa and Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi, his over-the-top antics in films like Half Ticket and Naughty Boy make me grit my teeth, they’re so unfunny.

Given Anirudha’s obvious expertise (and interest) in film music, I’d guessed the focus of this book would be Kishore’s music, with perhaps some attention also being given to his acting and directing.

What this book is, though, is far more wide-ranging. It is not just about Kishore’s songs and his films, but also about him on a personal level: as a brother, a son, a husband, a father. A boss, an associate, a friend, an irate citizen standing up for his rights against a tyrannical government.

Bhattacharjee and Dhar have arranged their book in chronological order, starting it sometime in the 1800s, by tracing Kishore’s ancestors, focussing importantly on his father Kunjilal Gangoly. They recount Kunjilal’s early life, his marriage to Gouri Devi, and their life in Khandwa (in present-day Madhya Pradesh), where Kishore was born. There are some delightful anecdotes in this section of the book (one, involving the young Kishore and a maths test that he did not ace, is particularly hilarious). Not only do the authors show Kishore’s deep attachment to Khandwa and its people—several of them close friends of Kishore’s—they are also able to show how Kishore’s early years in Khandwa and his affection for his hometown affected his cinema. Kishore ‘Khandwawala’s ‘badhiya khaale karaari gajak’ is not just a random line.

Elder brother Ashok Kumar’s entry into Hindi cinema, and in the years following this success, Kishore’s own attempts to break through, are described. The late 40s and early 50s, when Kishore, despite having sung for cinema, found himself only getting work as an actor, rather than a singer, segue into Kishore’s rise as a singing star: an actor who could sing, and sing well enough to sing playback for others… and with him becoming the ‘voice’ for major stars like Rajesh Khanna, there was no looking back. Whether in Hindi cinema, or live shows, or even in Bengal, what with his films, his poojo albums and his (sadly all too occasional) singing for Satyajit Ray.

Interwoven with his career is Kishore’s personal life: his four marriages, with a special focus on the first two. The first marriage with Ruma Guha, which ended in divorce; and the second marriage with Madhubala, which ended in her tragic death. In this context, what touched me most was the account of Kishore’s relationship with Madhubala: the sense of loving care, the desperation, the inevitability. It made me also marvel at just how good an actress Madhubala was, how well able to disguise the fact that she was so ill. (Just after reading the chapter on Chalti ka Naam Gaadi, I watched Paanch rupaiyya baarah aana—which, by the way, has an interesting Khandwa story behind it—and was both saddened and amazed by how radiant and effortlessly glorious Madhubala looks in it).

All (almost all?) of Kishore’s films, both the ones he sang and/or acted in, as well as the ones he directed feature in this book, the more landmark films (Chalti ka Naam Gaadi, Padosan, Door Gagan ki Chhaon Mein, etc) discussed in detail—not so much the film itself, but its making, interesting behind-the-scenes anecdotes, and so on. There are, too, the films that never got made, or sank without a trace, or were left only partly done.

It’s obvious that Dhar and Bhattacharjee have done a lot of hard work. The extensive end notes are nothing short of academic, and even if it wasn’t for that, the width and the depth of this book are proof enough. The angles from which Kishore is observed, the number of people (and their relationship with Kishore) whose words are quoted here: it’s clear that this is a labour of love.

And yet, it’s not hagiographic. Though it’s apparent that the authors admire Kishore immensely, they rarely go overboard with their praise. The overall picture one gets of Kishore is of an interestingly nuanced personality: a man who could be many things at once. Penny-pinching, or generous to a fault. Eccentric and uninhibited, or shy, even, of appearing onstage. Whacky, sensitive, a loyal friend, an infuriating (and refusing-to-be-co-operative) ‘adversary’.

That, really, is what I liked the most about this book: it does an excellent job of showing its readers who Kishore Kumar was. Not just the actor or the singer, but the man.

Was there something I didn’t like? Not really, though I do wish the editing had been marginally better.

Kishore -had heard of his many eccentricities- was created by circumstances that favoured Dev Anand initially & later Rajesh Khanna & Amitabh Bachhan

He could eclipse classically trained Rafi & Manna only because of those circumstances

However, many of his songs will last long

Have heard songs sung for Kishore Kumar, the actor, by Rafi

He was no shor , but a sound singer, though kishor in many ways

SP Balasubramanyam, though had no formal training in music, learnt nuances of the grammar of music as he sang more & more songs, while Kishore didn’t endeavour in that direction

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree about him being no ‘shor’. While for me personally Rafi is just slightly more of a favourite, I like Kishore a lot too. There are a large number of songs that he’s sung really well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many of Kishore’s songs live long particularly as he had perfectly reflected moods either in melancholy(koi humdum na raha for example) or joy as in Dekha Dekha Na Haye Re & these two are not exhaustive

LikeLike

Many of Kishore’s songs live long particularly as he had perfectly reflected moods either in melancholy(koi humdum na raha for example) or joy as in Dekha Dekha Na Haye Re & these two are not exhaustive

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely review, dear Madhu.

This will be the perfect gift for my brother, who has his birthday in March and is a big fan of Kishore Kumar.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the perfect gift for a Kishore fan, Harvey. :-) Highly recommended, and I hope your brother enjoys it as much as I did.

LikeLike

I feel slightly better now, Madhu. :) I had the book for so long before I reviewed it, too.

Lovely review, as usual.

(Welcome back. I’ve missed a few of your reviews, so will catch up on it soon.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed this review, Anu. Thank you for reading. And welcome back to you, too. :-)

LikeLike

I like Aniruddha da’s books usually. They are well researched and detailed- something which should be a norm but is more often than not an exception here unfortunately. So, it’s good that the legacy of Kishore Kumar is safe in the hands of such an author. For Kishore Kumar deserves nothing less.

Kishore Kumar is quite possibly the definitive Bollywood icon. One can even go to the extent of calling him the personality that best defines Bollywood- joyous, fun, frothy and filled with lively (and moving) song and dance. These are the traits that are best identified with Bollywood across the world. And nobody embodied them better than Kishoreda. For he brought to each of these traits a tremendous degree of inventiveness and originality- characteristics which are often missing in many an other great artist.

But then Kishore Kumar wasn’t merely a great, he was a genius!

People often forget that here is a man who had the box-office record of an actor like Shammi Kapoor, singing hit (and impact) record like a Mohd Rafi and a comedian track record like that of a Johnny Walker and a Mehmood! Additionally alongside Bhagwan Dada, he was also a pioneer of dance among heroes in our cinema. Such versatility are clearly proven by his records too. Numbers seldom lie. And they most definitely don’t do so in Kishoreda’s case.

The stats clearly point out that here was a maverick that should not have existed. But like all great Acts of God, did! And Indian cinema was lucky to have him. Indeed, given his wholesome and comprehensive brilliance, I would state that Kishoreda is still under-celebrated!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Madhu, I read the review on Goodreads but missed it here. Not following mails / sm for quite some time. Thanks again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No worries, Anirudha! Same review. :-)

LikeLike

Hi Dusted Off,

I have been meaning to ask you this for a while – do you have a list of books you have read / reviewed related to Bollywood music, such as this book here?

It’s been on my list for a few years to read such books related to golden era playback singers, music directors, lyricists etc.

I recently got a copy of Kundan: Saigal’s Life & Music by Sharad Dutt & Jyoti Sabharwal but haven’t started reading it yet.

Do you have other books you can recommend?

Thanks,

Pratick

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read the KN Saigal book, but over the years I’ve read and reviewed quite a lot of biographies of film personalities. Not all of these are singers or composers, but you can have a look here:

https://madhulikaliddle.com/?s=book+review&submit=Search

LikeLike