The 1936 Hindi film Jeevan Naiyya begins with a telephone conversation. An engaged couple, very much in love with each other, whispers sweet nothings on the phone. It’s all a bit awkward, and the young man in particular comes across as distinctly uncomfortable with all this koochie-kooing. This is not quite the mellifluous, effortless romance of a Jalte hain jiske liye, but it is, in its own way, a landmark scene. Because this is the very first onscreen appearance of a young actor who went on to become one of Hindi cinema’s biggest stars: Ashok Kumar Ganguly, better known simply as Ashok Kumar.

Dadamoni had abandoned his law studies in early 1934 to seek a career in cinema. Not as an actor; he wanted to be a director. Ashok Kumar approached his brother-in-law, Sashadhar Mukherjee (who would go on to be one of Hindi cinema’s great film-makers), then working with The Bombay Talkies, the premier film studio established by Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani. It was Mukherjee who brought Ashok Kumar to Bombay, where he joined The Bombay Talkies as a technician in the sound department… until Himanshu Rai badgered him into acting in Jeevan Naiyya, following the sudden departure of the leading man, Najmul Hussein (The story goes that Najmul Hussein and Devika Rani had eloped, and while Sashadhar Mukherjee was able to persuade her to return to Bombay and to the film, Najmul Hussein was left high and dry).

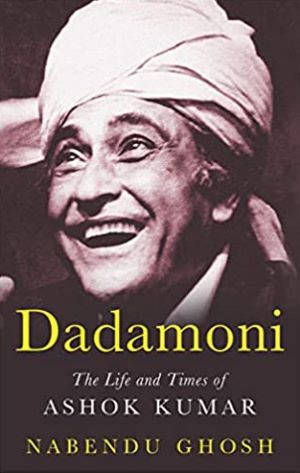

How this reluctant actor, jittery and inept at first, and with a thin voice that is almost jarring—ended up as one of Hindi cinema’s most popular and biggest stars, is the subject of Nabendu Ghosh’s Dadamoni: The Life and Times of Ashok Kumar (Speaking Tiger Books, 2022).

Ghosh, a film-maker, writer and actor, who wrote the screenplay of classics like Sujata, Bandini, Devdas and Parineeta, was probably among the people most qualified to write Ashok Kumar’s biography: not only was he there working alongside Dadamoni in many films through the 40s and 50s, he was also an important part of Dadamoni’s life: a fellow Bengali, a confidant, a friend. In Dadamoni, he sets out to trace the rise of Ashok Kumar, his journey from his birthplace in Bhagalpur, to the silver screen.

The narrative follows Dadamoni through the early years of the ‘talkies’, when playback singing had not yet become popular and Ashok Kumar was obliged to sing his own songs onscreen; the years when he studied the art and craft of acting in an attempt to create his own natural style; and beyond. The burgeoning popularity that saw the runaway success of films like Kismet (1943). The many films, the varied characters, the sometimes offbeat roles (Kismet, with its anti-hero; Mahal, with its tormented protagonist; and so many others). Past the years of being hero, when Ashok Kumar moved into character actor roles: comic, poignant, avuncular—and always so natural, so believable as the character he was playing.

Ghosh discusses, along with a brief synopsis, some of Ashok Kumar’s major films across the years, how they were made, and what Dadamoni brought to them. Before that, though, Ghosh provides some interesting insights into the Ganguly family’s history, and the home in which the brothers (Ashok, Anoop and Kishore) grew up. There are equally interesting bits of trivia about Dadamoni’s initial foray into cinema; how his association with Bombay Talkies changed over time; even how he got saddled with the epithet of ‘Dadamoni’.

The hobbies and talents that Ashok Kumar nurtured also find mention in Dadamoni. Some, like his proficiency in homeopathy, I knew about; others, like his ease with languages (he knew at least eight languages) and his adeptness at concocting amusing rhymes which he would rattle off, in conjunction with his obliging children, may be less common knowledge. Interestingly enough, I discovered through this book, that Ashok Kumar was a good friend of Iftekhar’s—and it was through Iftekhar, who was learning French, that Ashok Kumar also decided to learn the language. What’s more, Iftekhar (himself a fine painter) helped nurture Ashok Kumar’s talent as a painter. A self-portrait of Ashok Kumar’s is among the many interesting photographs and other images that form part of this book.

If that’s a good way of understanding the man behind the actor, there are interesting anecdotes, too, from Ashok Kumar’s career that help. There is, for instance, an amusing (if mortifying) series of episodes from the shooting of Jeevan Naiyya, when Ashok Kumar’s ham-handed bumbling caused much distress, both to him and to others (a fellow actor even fractured a leg thanks to Ashok Kumar). There is a poignant example of Dadamoni’s dedication to his work, in the form of a memorable behind-the-scenes moment from Humayun (1945), and a testimony to his popularity from when, along with Manto, he was driving through a tense Muslim-dominated neighbourhood of Bombay at night, and the car came to a stop amid thronging crowds.

Perhaps because Nabendu Ghosh was a scriptwriter, he chooses to use dialogue to narrate some of the episodes in this book. While it’s not a technique that often works, Ghosh manages to pull it off and produce a charming, engrossing biography of Dadamoni. One wonders, though, if this is not completely unprejudiced: barring a fleeting mention of Ashok Kumar’s hot temper (a mention, too, which devolves into humour), there is nothing here about the actor’s failings. Did he not have any, or is Ghosh looking at him through rose-tinted glasses? I cannot tell.

Nabendu Ghosh’s book is sandwiched between a foreword by Bharti Jaffrey (Ashok Kumar’s daughter) and an afterword by Ratnottama Sengupta (Nabendu Ghosh’s daughter). Taking those, as well as the selected filmography at the end, into consideration, the complete length of Ghosh’s text is only about 125 pages: possibly inadequate for a detailed biography, and the more diehard Dadamoni fans will probably find this too tantalizingly short a glimpse of their idol. Longer and a more in-depth analyses of his acting style, perhaps more discussions of some of his later roles, might have helped.

Even then, Ghosh manages to cover a good deal of ground, and leave the reader with a satisfying enough glimpse of Ashok Kumar. Equally, he is able to provide an interesting snapshot of film-making in the 30s and 40s, a period and a style very different from even what it was back in the 90s, when Ghosh initially wrote Dadamoni.

A very readable book about a very watchable actor. If you like Ashok Kumar, this one’s a great introduction to his life and his career.

This book was first published in 1995 by Harper Collins. I remember buying the same during the Calcutta book fair in 1996. It has some nice-to-know stories. Led me to make multiple trips to Bhagalpur. And in the process, unearthed some stories as well…

LikeLike

Do those stories find a mention in your books? :-) Or are they still unpublished?

LikeLike

Ah, some would be there in some time. Hopefully. Fingers crossed :)

LikeLike

Wonderful. I will look forward to that!

LikeLike

Now, this sounds very, very interesting, Madhu, and I’m so glad you reviewed it – positively, that too. In a strange coincidence, I’d been reading up about Nabendu Ghosh recently. What a storyteller he was! Am putting this on my list of books to buy in India right away! Thank you for this. :)

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Anu, and thank you for reading! I really enjoyed this book – and, one thing which I appreciated (and which I actually only just realized, when I read your comment about Nabendu Ghosh being a great story-teller): he does not push himself into this narrative, unlike some other biographers I’ve read (I think you know too, whom I mean…). He’s there, as a witness, here and there, when he’s recounting an anecdote, but there’s no taking of credit for Ashok Kumar’s success, no trying to piggyback on the greatness of the subject of the biography.

LikeLike

but there’s no taking of credit for Ashok Kumar’s success, no trying to piggyback on the greatness of the subject of the biography.

That makes me even more interested in reading this. If you have any other recommendations for books, let me know, please. I’m making a list of books to buy on my trip there.

LikeLike

Another book which I really, really enjoyed was Shrabani Basu’s The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer – a very readable account of Arthur Conan Doyle’s defence of George Edalji.

LikeLike

Ooh, thank you. That sounds very interesting. By the way, have you read The Case That Shook The Empire? It’s by Raghu Palat and Pushpa Palat. It’s wonderfully researched and was very interesting to read.

LikeLike

Also, Saba Dewan’s Tawaifnama…

LikeLike

I haven’t read either of those, though I’ve heard of Tawaifnama. Thank you, Anu! Adding both of these to my list.

LikeLike

Madhu,

This seems to be an interesting book. Your reference to Manto and Iftekhar in the book rung a bell. I have Manto’s “Stars from Another Sky” in which one of the pen portraits is on Ashok Kumar. He mentions the incident during the riots. He also mentions another aspect of Ashok Kumar which can be discussed only in men’s cloak room. He had a way of looking at everyone with one-coloured prism. One was not sure where he was in his periods of sanity and insanity.

In ‘Ye Un Dinon Ki Baat Hai’ Iftekhar has written on Ashok Kumar and Kishore Kumar. He must have written it in Urdu for ‘Shama’ magazine, but English translation is excellent.

You have written a very nice review.

LikeLike

I have been wanting to read Manto’s Meena Bazaar(which, if I’m not mistaken, was the original for Stars from Another Sky?), since I’ve never read anything of Manto’s other than his fiction and a brief essay on Sitara Devi, which I’d read in translation. Yeh Un Dinon Ki Baat Hai is also on my To-Be-Read pile, ever since Anu reviewed it.

LikeLike

Nice write up. Just want to point out a minor oversight. Ashok Kumar’s actual name was not Ashok Kumar Ganguly but Kumudlal Ganguly. Ashok Kumar was the screen name given to him. Anoop Kumar’s actual name was Kalyan Kumar Ganguly and Kishore Kumar’s actual name was Abhas Kumar Ganguly.

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked this review, thank you. And of course you’re right – I worded that badly (I simply went with the commonly used name, instead of also clarifying what his real name was). Nabendu Ghosh does explain what the three brothers’ names were.

LikeLike

Being a big fan of Ashok Kumar, I would definitely love to read it though you have earnestly clarified that it’s far from perfection and leaves a lot to be desired. This post of yours mentions Ashok Kumar’s name as Ashok Kumar Ganguly. I had read somewhere that his real name was Kumud Lal Ganguly (and Kishore Kumar’s real name was Abhas Kumar Ganguly). Hearty thanks for providing an insight into the book which appears to be a must read for the fans of the legendary actor as well as those who might be interested in knowing about Indian cinema across many decades and different times.

LikeLike

Yes, you’re right, Ashok Kumar’s real name was Kumud Lal Ganguly – I should have worded that better. Nabendu Ghosh does mention the real names of all three brothers.

It’s a good book, actually. Not “leaves a lot to be desired” at all. :-)

LikeLiked by 1 person