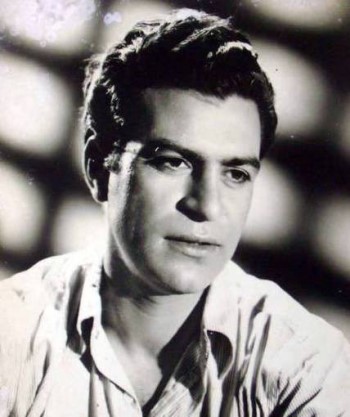

Today is the birth centenary of one of a handful of Hindi film actors who managed to cross from one type of role to another—again and again. Like Ajit, Pran, and Premnath (though not in the same league as them, when it came to success and popularity), Sajjan Lal Purohit—better known simply as Sajjan—appeared in leading roles in several of his early films (including, notably, in Saiyyaan, where he acted opposite Madhubala), then drifted into supporting roles (as Dev Anand’s sculptor friend in Paying Guest; as Mini’s father in Kabuliwala; and more), and eventually into villainous roles (in April Fool, Aankhen, Farz, etc).

Tag Archives: film review

Dillagi (1949)

A couple of months back, a blog reader had remarked that Hindi cinema, during the 1930s and 40s, seemed to have a fairly unimpressive-looking lot of leading men. The good-lookers, was the theory, were the ones that came later, though there had been a very few rare exceptions, like Shyam.

While I didn’t agree that most of the leading men of the 1930s and 40s were ugly (or at best, plain), I did agree about Shyam. Shyam was one of those very handsome actors who, with his impressive height and build added to his charisma, could have posed a serious threat to the triumvirate of Dilip Kumar, Raj Kapoor, and Dev Anand. Sadly, Shyam died tragically young, just 31 years old, after sustaining a head injury caused by a fall from a horse during the shooting of Shabistan in 1951.

Born in Sialkot on February 20, 1920, Shyam Sunder Chadha ‘Shyam’ debuted in a Punjabi film, Gowandhi (1942) and continued to work sporadically in cinema over the next few years. After Partition, Shyam shifted to Bombay, and that was when his career really took off. Over the next four years, he worked in a slew of films, including some big hits like Dillagi, Samadhi, and Patanga. One can only speculate on what trajectory his career might have taken had he lived into the 60s. (Interestingly, Shyam was a very dear friend of Sa’adat Hasan Manto: it was a friendship that outlasted Partition, and Manto was deeply affected when Shyam passed away).

I hadn’t realized, back in February this year, that it was Shyam’s hundredth birth anniversary. But the year is still the same, so in celebration of Shyam’s birth centenary year, a review of one of his biggest hit films. In Dillagi, Shyam acted the role of Swaroop, a dashing young man who falls in love with a village girl named Mala…

Zindagi ya Toofaan (1958)

After many years of telling myself I should read Mirza Hadi ‘Ruswa’s Umrao Jaan Ada, I finally got around to reading a Hindi translation a couple of weeks back. This turned out to be an underwhelming experience (more details here, on my Goodreads review of the book), but it impelled me to read a synopsis of Umrao Jaan Ada. I ended up reading, too, about the screen adaptations of the book (which is regarded by many as the first Urdu novel), and was surprised to discover that, besides the Rekha-starrer and the (much later) Aishwarya Rai-starrer, there were two other films, both released in 1958, based on Umrao Jaan Ada. One was Mehendi; the other was Zindagi ya Toofaan. I haven’t got around to watching Mehendi yet, but the fact that one of my favourite actresses of the 50s, Nutan, starred in Zindagi ya Toofaan, made me eager to watch this one.

Hulchul (1951)

Today is the hundredth birthday of one of India’s greatest and most popular dancers of yesteryears. Sitara Devi was born in Calcutta on November 8, 1920, to a father who was a Sanskrit scholar and also both performed as well as taught Kathak. Her mother too came from a family with a long tradition in performing arts, so it was hardly a surprise that from a very young age, Sitara (her birth name was Dhanalakshmi) began to learn Kathak. By the time she was ten, Sitara was giving solo performances; two years later, at the age of twelve, she (having since moved to Bombay with her parents) performed onstage and so impressed film-maker/choreographer Niranjan Sharma that he recruited her to work in films.

Unlike several other skilled danseuses—Vyjyanthimala, the Travancore Sisters, Waheeda Rehman, etc—Sitara Devi did not let cinema take over her dance completely. She danced in a number of films, through the 40s and right up to Mother India (1957), which is believed to be her last onscreen appearance. She continued to give stage performances, even performing at New York’s Carnegie Hall and at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

Sitara Devi wasn’t merely a film actress; she was also a great dancer. I wanted to pay tribute to her through a review of one of her films, and decided I’d choose Hulchul, which I wanted to watch for other reasons as well (more on this later).

The Hill (1965)

I got to know of the passing away of Sean Connery through social media. I logged in to Facebook on the evening of October 31, and saw several people posting tributes to the ‘best Bond there ever was’. One person in my newsfeed posted a still from The Name of the Rose, but even she couldn’t resist the temptation to also talk of Connery being the best James Bond.

I suppose that is how Connery will go down in popular memory: Bond, after all, is a hugely popular character, and Connery, I will admit, made for a suave and very attractive Bond. But Connery could be so much more, as this poignant tribute from Anu discusses.

I liked the James Bond films when I was younger; I saw pretty much all of them. In recent years, though, I’ve begun to not enjoy them as much, mostly for their shallow portrayal of women. So, to pay tribute to Connery, I decided not to attempt a review of a Bond film: I knew, even without rewatching From Russia With Love, Goldfinger, or the other films Connery starred in as Bond (I had already reviewed Dr No, here)—I knew I would end up cringing at the sexism in the film.

Therefore, this film, which was made around the same time Connery was Bond. But oh, so different from Bond.

Light in the Piazza (1962)

Earlier this year, when Olivia de Havilland passed away, someone I know was reminiscing about her films and mentioned Light in the Piazza as being a particular favourite. I had never even heard of Light in the Piazza, let alone anything else, so I decided to have a look. It did turn out to be a mostly enjoyable film, but I didn’t find it worthy of being a tribute to Olivia de Havilland (what I reviewed instead as a tribute was this).

But Light in the Piazza is worth talking about, because it’s an unusual film. Unusual in its subject matter, and unusual in the fact that its leading lady acts her age: Olivia de Havilland was in her mid-forties when she acted as Meg Johnson, and she brings to the role all her wealth of experience.

From Here to Eternity (1953)

1941.

Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) arrives at a military base in Hawaii and presents himself before the commanding officer, Captain Dana Holmes (Philip Ober). The captain is a boxing enthusiast, and he’s licking his lips at the thought of having added one of the army’s best boxers to his clutch: Prewitt is a famous middle-weight, isn’t he. No sir, Prewitt says. He was; he doesn’t fight now. Not after that incident—Holmes obviously knows what Prewitt’s alluding to, but we get to know only later, when Prewitt meets and falls in love with a prostitute named Lorene (Donna Reed).

Jaadoo (1951)

There are several reasons why I decided to review this film, even though it’s not a particularly impressive one. For one, it’s one of the rare Indian films set outside India and the Middle East (more on this later). For another, its music by Naushad, who (I would have thought) would not have been the most obvious choice to compose music for a film that’s distinctly Latin in tone. And, because this is a film I’ve long been wanting to see—ever since I first watched Lo pyaar ki ho gayi jeet on Chitrahaar as a pre-teen.

Continue readingJagriti (1954), Bedari (1956)

One review suffices for two films, really. Jagriti was an Indian film, Bedari a Pakistani one. Why I say one review suffices is because Bedari was a blatant copy of Jagriti: so blatant that when Pakistanis cottoned onto the fact that it was a copy, there was a furore which resulted in the Federal Board of Film Censor in Pakistan banning Bedari.

I’ll discuss the synopsis by looking at Jagriti, since Bedari used exactly the same plot, down to the scenes.

Jagriti begins by introducing us to the very wild teenager Ajay Mukherjee (Raj Kumar), who spends his after-school time gallivanting around the village with his gang of equally wild friends. They steal mangoes from an orchard and leave the irate gardener with a bump on his head; Ajay slips onto a ferry and deprives a banana-seller of an entire day’s worth of bananas.

By the time Ajay gets home, his uncle (Bipin Gupta) has been besieged by some very upset villagers. He’s had to soothe them, pay up their damages, and promise that the situation will be amended.

Born Free (1966)

Some of you may know about my six-year old daughter, the Little One (the ‘LO’), whom I’ve written about occasionally, in the context of our travels.

This time, the LO stars in one of my film reviews. Because Born Free happens to be the first film which fits my blog’s timeline and which the LO watched along with me. We’ve watched other films in theatres, and (over the course of the lockdown) at home, but all of them have been animated films or Harry Potter. But this last Saturday, reliving our trip to Kenya at the beginning of this year, I was reminded of Joy Adamson (whose paintings we saw at the Nairobi National Museum), and I decided we should watch Born Free.