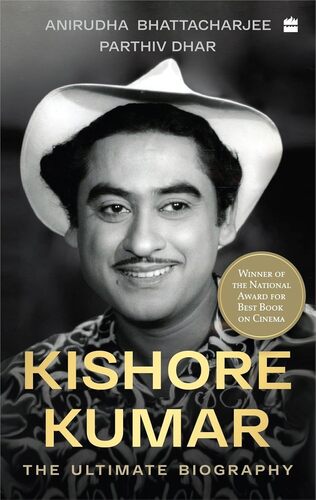

Anirudha Bhattacharjee—who has gifted me quite a few of his books on Hindi cinema in the past—sent me this book last year. I accepted his offer of the book for two reasons. For one, there isn’t a book by Anirudha that I have not enjoyed. For another, I really like Kishore Kumar the singer.

Note that disclaimer: the singer. When it comes to Kishore the actor, I’m not so sure. While I find him quite enjoyable in films like Pyaar Kiye Jaa and Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi, his over-the-top antics in films like Half Ticket and Naughty Boy make me grit my teeth, they’re so unfunny.

Given Anirudha’s obvious expertise (and interest) in film music, I’d guessed the focus of this book would be Kishore’s music, with perhaps some attention also being given to his acting and directing.

Continue reading