I have decided it’s high time I began rewatching some of the old Hindi films I last saw when in my teens (or, in some cases, even before that). Back then, all our film viewing used to happen on India’s sole television channel, Doordarshan, which would telecast Hindi films every weekend, and sometimes in between as well. Most of the films were old classics, and I have fond memories of first viewings of films which became firm favourites almost from the get-go: Junglee, Teesri Manzil, Nau Do Gyarah, Dekh Kabira Roya, Woh Kaun Thi?, Mera Saaya…

There were also films that I watched (we watched everything, there was such a paucity of options for entertainment) but which I ended up not liking. Or, as in the case of Chitralekha, not really understanding. I guess this was a simple case of being too young, too immature, to grasp the niceties of a film that wasn’t the standard masala entertainer.

About time, I thought, I saw this one again.

Kidar Sharma, who directed Chitralekha, had already made this film (based on a novel by Bhagwati Charan Verma) earlier as well. The 1941 Chitralekha starred Mehtab (who of course later married Sohrab Modi) and the juiciest bit of information about the film is that it featured a bathing scene (Cineplot used to have an article about this, an excerpt from Kidar Sharma’s autobiography, but since Cineplot now seems to be sadly defunct, that’s gone). Kidar Sharma did say, from what I recall of his autobiography, that the original Chitralekha was far superior to the 1964 remake.

But the 1941 film is, I think, gone—or at least not available for viewing online, though there are songs and stills galore. I may as well watch the 1964 Chitralekha, I decided, since that was the one I had hazy recollections of watching as a child.

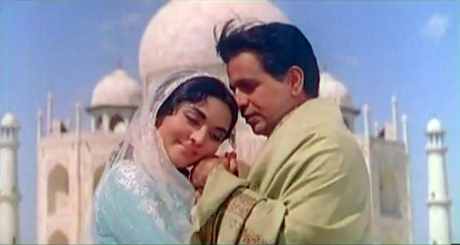

The story is set in Pataliputra during the heyday of the Gupta Empire. Aryaratan Samant Beejgupt (Pradeep Kumar), a high nobleman, has just returned to Pataliputra after a sojourn elsewhere. Beejgupt’s arrival in the city is greeted with anticipation: his fiancée Yashodhara (Shobhna) is shyly hopeful that this time he will marry her.

Continue reading →